Written by Piergiuseppe Fortunato, UNCTAD Economist

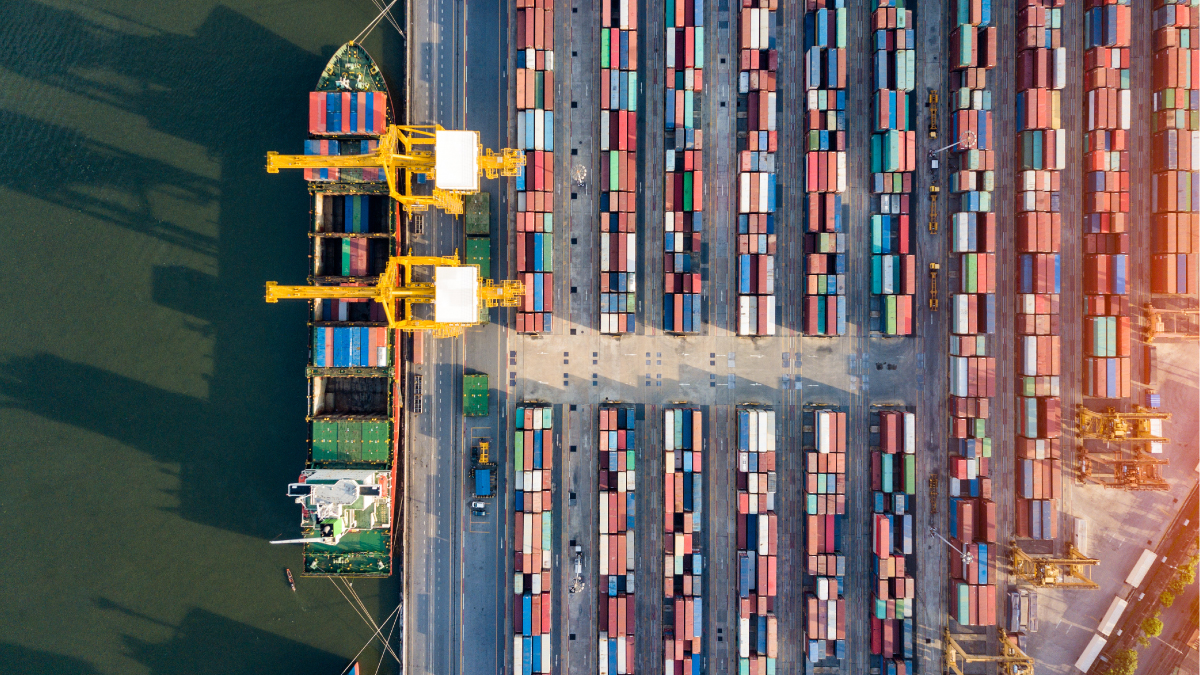

The COVID-19 crisis has amplified profound fault lines in the functioning of global value chains (GVCs) and exposed the fragility of a model characterized by high interdependencies between leading firms and suppliers located across several continents.

All at a time when timely production of critical products is more important than ever, amid a pandemic that has locked down vast parts of the planet and limited economic activities in an unprecedented way.

Trends in technology and globalization, and the regulatory framework in place since the early 1990s, have fostered massive offshoring of low-value-adding and wage-sensitive activities at the bottom of value chains to developing economies with limited productive capacities.

On the contrary, intangible tasks such as research and development, design, marketing and branding, based on unique resources and capabilities that are difficult to acquire, are largely still performed in headquarters, generating superior returns, often in the form of rents.

Fragility revealed

This model, however, revealed all its fragility to external shocks when COVID-19 struck.

The persistent uncertainty related to the shift of the epicenter of the pandemic from region to region, and the parallel instability affecting production costs, make it difficult to resume business on a global scale, leading many firms to reduce or stall their production activities.

At the same time, temporary surges of demand for certain critical commodities have not been met by increased supply since, under the current model, dramatic changes in the scale of production might not be easily absorbed after a return to normality.

This is testified by the shortage of much-needed products like masks and ventilators.

Long before COVID-19, industry 4.0 technologies were already fostering a reorganization of GVCs involving significant relocation (and reshoring) of productive activities.

From a lead firm perspective, industry 4.0, especially automation, unlocks new labour-saving technologies, which could potentially reduce reliance on low-skill labour in manufacturing and therefore reduce the benefits of offshoring.

Automation also has important implications for the global geography of production, as value chains will become more regional in nature, moving closer to consumer markets where ecosystems are more supportive to business.

COVID-19 will reinforce relocation and reshoring trends

Confronting COVID-19 could accelerate some these trends. Both automation and reshoring allow for more flexible adjustment to changing demand, mitigating firms’ risks in the event of a pandemic or other external shocks.

Furthermore, supply chain and travel disruptions caused by COVID-19 might undermine economic integration and encourage self-sufficient economic systems, at least in strategic sectors such as medical equipment and drugs, or the production of inputs for assembling sophisticated machines, the final production of which still occurs in high-wage countries.

This tendency is reflected in the growing number of temporary export bans and restrictions on critical goods enacted by numerous countries after the outbreak.

It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that most analysts concur that the current pandemic will reinforce relocation and reshoring trends.

With most economies under full or partial lockdown and with trade and investment contracting, the future of offshoring is more uncertain than pre-COVID-19.

The World Trade Organization predicts a trade fall of between 13% and 32%, while UNCTAD estimates a foreign direct investment contraction of 30% to 40% during 2020 and 2021.

The reshoring challenge

Reshoring is challenging for the recipient economy. The process can cause significant economic and social costs much beyond the immediate job and business turnover losses.

Relocations, in fact, trickle down rapidly to the local economy, affecting the local supply chain, the offer of local services and (in the medium and long run) the quality of infrastructure, unless targeted strategies are put in place.

Reconversions are possible but these processes need to be closely monitored to ensure effective transformations and revamping of previously industrialized areas.

However, while multinational corporations (MNCs) will certainly rethink their strategies and give even more relevance to automation and reshoring to mitigate risks, it is unlikely that entire supply chains will be automated, at least in the near future.

The automation of certain components may not be feasible or even desirable, for example due to shortages of skilled workers, while, in other cases, MNCs have precise information on the suppliers involved only up to two or three levels down the production line.

This lack of information, in turn, often linked to hidden subcontracting like in the case of the garment industry, may create additional obstacles to reshoring.

Furthermore, other developments, including the growing demand for mid-range consumer goods like electronics and apparel in emerging markets, could slow down the reshoring trend.

In fact, especially in labour-intensive GVCs, MNCs might find it economically more profitable to maintain their production facilities close to the (new) final markets, where labour costs are low and the supply of workers able to operate complex machines is not enough to make automation viable.

In such a complicated and rapidly changing environment, developing countries need to concentrate their efforts around three strategic areas of policy action.

More diversification

They should focus on diversification away from traditional tasks and activities, which can be affected by automation.

The narrow focus on manufacturing must give way to more emphasis on new sectors like the creative and digital economy sectors.

Some of the sectors that have benefited the most from the COVID-19 crisis are those that can deliver online and on-demand services.

Stronger regional value chains

Strengthening regional value chains should be a priority for developing countries to diversify risk, reduce vulnerability, increase resilience and foster industrial development.

By identifying and maintaining horizontal and vertical linkages, regional pacts can ensure that small firms cooperate to reduce transaction costs and benefit from economies of scale.

They can also help favour connectivity among different specialized providers whose inputs are directly integrated in the supply chain.

Furthermore, as recently proposed by UNCTAD, a South-South cooperation initiative on health, health research and related areas is needed.

More state regulation

Governments need firms to internalize the various externalities and spillovers that their investment and innovation decisions produce for the communities and societies where they operate.

This should be done by introducing explicit regulatory and governance frameworks and not simply relying on corporate social responsibility. This is all the more important in sectors put at risk by trends of reshoring and automation.