By Paul Akiwumi, Director of Division for Africa and Least Developed Countries, UNCTAD

Illicit financial flows rob African countries of capital they could invest in development priorities like education / ©poco_bw

Curbing illicit financial flows (IFFs) can help African countries mobilize capital to finance the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other national priorities.

Our new UNCTAD policy brief on combating IFFs in Africa provides guidance on how governments on the continent can do so.

Financing shortfalls continue to hamper progress towards the SDGs, the African Union Agenda 2063 and the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Investment in national development priorities, such as infrastructure and education, is often wanting as well. Heavy costs associated with weathering, and then recovering from the COVID-19 crisis, further widen the overall financing gap.

Prospects for new inflows is limited. Official development assistance (ODA) to Africa has stagnated for a decade at around $30 billion per year and donor countries are unlikely to increase their aid commitments as they spend on COVID-19 recovery packages at home.

Meanwhile, UNCTAD predicts that foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa will plunge from $45 billion in 2019 to between $25 and $35 billion in 2020, with a recovery not expected until 2022.

Outflows are a potential source of new funds

In this context, African countries should look for new funds from a counterintuitive source: outflows. UNCTAD estimates that $88.6 billion per year leaves the continent in the form of capital flight, which is wealth sent and held abroad.

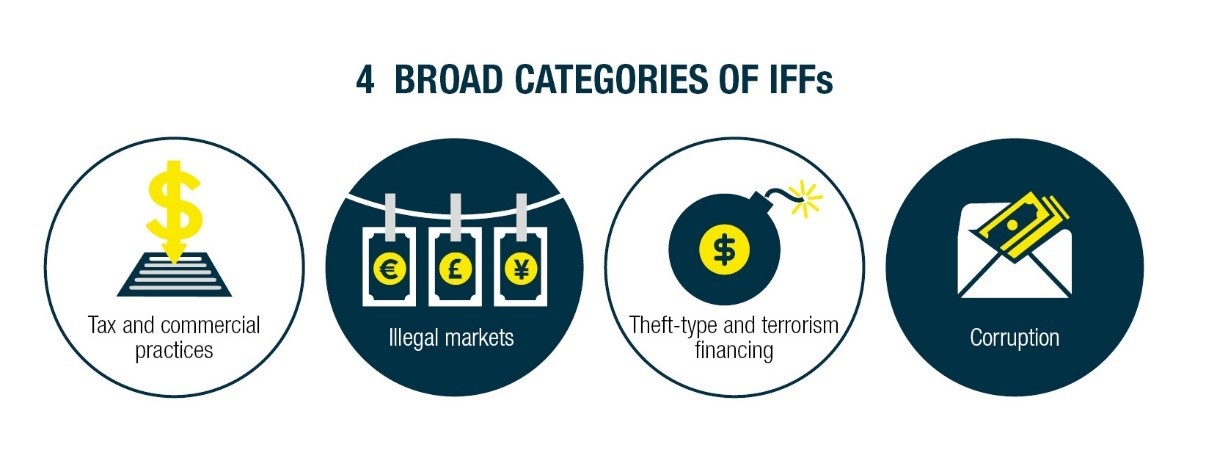

Some capital flight leaves through legal channels while others are proceeds from IFFs –movements of money and assets across borders that are illegal in source, transfer or use.

They include criminal activities, such as corruption or smuggling; commercial practices, such as the misinvoicing of trade shipments; or tax practices, such as the abusive use of transfer pricing. Commercial and tax IFFs are often linked to tax evasion strategies, designed to shift profits to lower-tax jurisdictions.

As most countries in sub-Saharan Africa are dependent on exports of raw commodities, commercial flows of commodities are a focal area in the study of IFFs.

UNCTAD estimates that the persistent gap between what African countries report as commodity exports and what their trading partners report as imports (i.e. export underinvoicing), was at least $40 billion in 2015, with gold exports representing 77% of the total.

As an illicit outflow, trade underinvoicing contributes to capital flight and lost taxes, widening the development financing gap in Africa and eroding countries’ resilience to crises, such as COVID-19.

Curbing IFFs can help plug funding gap

Curbing capital flight and IFFs, as part of a wider effort to improve tax collection, could raise tax revenue in African countries by an additional 3.9% of GDP, or $110 billion a year.

Although this sum will not close the financing gap, it would give African governments invaluable fiscal space to respond to the COVID-19 crisis and invest in future priorities.

To curb IFFs and stem some of the leakage, policymakers must overcome a number of challenges. Collecting data on illicit activities is inherently difficult and is compounded by the sparsity of data on intra-African trade, especially over land borders.

African governments must therefore invest in collection infrastructure, to collect more and better data. IFFs being cross-border activities, governments must also cooperate at the regional level, aligning policies and sharing data on sectors at risk of IFFs, such as extractives, telecommunications and banking.

Compounding the problem of data scarcity, commercial IFFs are woven within a legal complex of, for example: bilateral agreements; concessions for natural resource exploitation; and commercial contracts.

How to roll out a long-term approach

Therefore, a long-term approach to enforcement must not only scrutinize individual deals, but also redress loopholes in treaties and legal frameworks. African governments can draw from best practices and model treaties and contracts.

They can also leverage multi-stakeholder oversight of the exploitation and trade of natural resources, engaging existing structures in member countries of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Capital flight, IFFs and base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) have a disproportionate impact in Africa, draining scarce resources from the continent that could be invested in sustainable development.

Nevertheless, African countries are not yet sufficiently engaged in the international tax reform process. As well as cooperating on policy and data, they should aim for common positions on OECD/G20 proposals and make tax competition consistent with protocols of the AfCFTA.

More detailed recommendations are available in our policy brief.