Article No. 45 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°85 - First Quarter 2020]

The Third Greenhouse Study of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) estimated that international shipping accounted “for about 2.2% of the total global anthropogenic CO2 emissions for 2012, and that emissions from international shipping could grow between 50% and 250% by 2050 mainly due to the growth of the world maritime trade”. In 2018, IMO members agreed “to reduce the total annual GHG emissions by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008” as part of the “Initial IMO Strategy on reduction of GHG emissions from ships”.

The private sector-led “Getting to Zero Coalition” points out that to “reach this goal and to make the transition to full decarbonization possible, commercially viable zero emission vessels must start entering the global fleet by 2030”.

The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) and other private sector organizations propose a fund to help cut emissions by accelerating “the development of commercially viable zero-carbon emission ships by the early 2030s.” UNCTAD collaborates with the IMO and private-sector initiatives in the analysis and capacity building to support developing countries in preparing for the required shift in technology and fleet renewal.

In order to estimate how long it would potentially take to replace the currently existing fleet with new ships – which would ideally use alternative fuels – in this article, we look at past scrapping patterns and show how future demolitions would develop if ships continued to be demolished at the same age as in the past. Put differently, we apply the life expectancy of the ships that were demolished in recent years to better understand the possible life expectancy of today’s ships. This life expectancy is obviously not cast in stone, but can be influenced by various factors, which we will also discuss below.

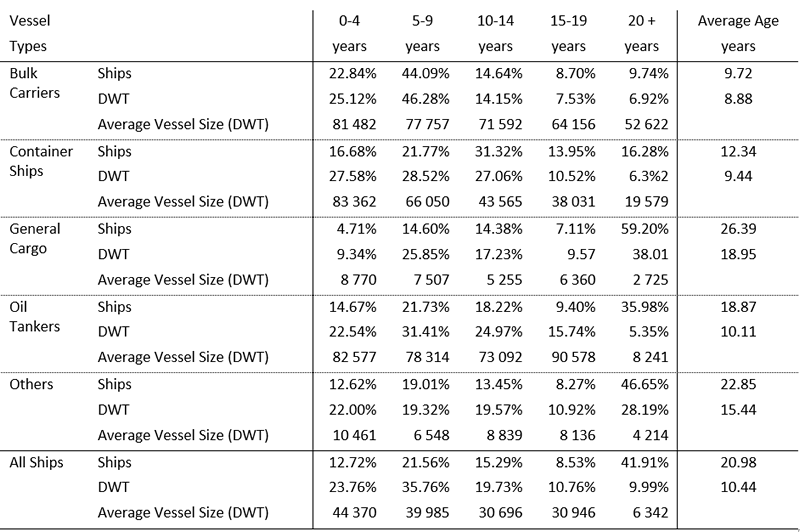

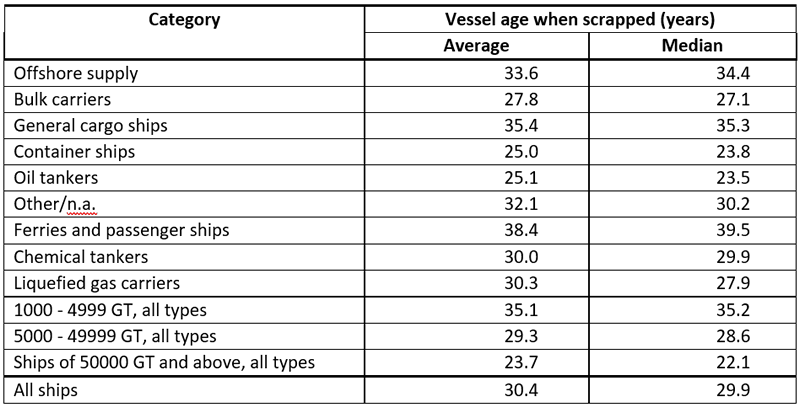

We start out by looking at the structure of the world fleet at the beginning of 2019 in age brackets (Table 1) and the age of the vessels at the year of scrapping during the years 2016-2018, disaggregated into size brackets and vessel types (Table 2).

Table 1: Age distribution of world merchant fleet by vessel type, beginning of 2019

Table 2: Average and median age of ships when scrapped in 2016, 2017, and 2018

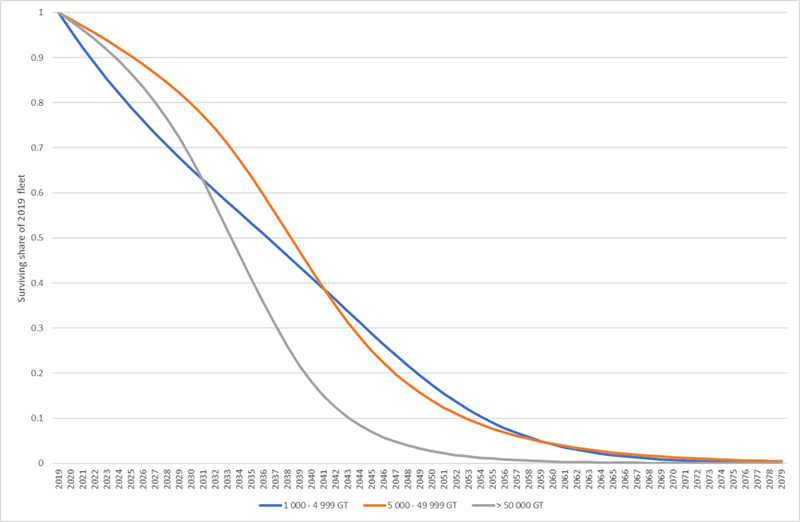

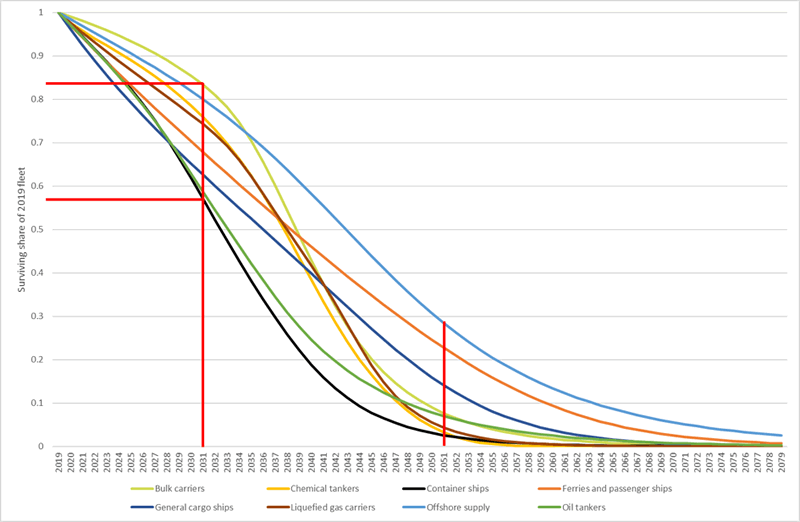

We then apply the age-dependent scrapping probability to the currently existing fleet to estimate when the ships in service at the beginning of 2019 would be demolished, if this distribution remained the same as that of the previous three years (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Distribution of the projected remaining share of the currently existing fleet, beginning of year, by vessel size

Today's older ships are - on average - smaller than the more recently built vessels, especially the latest large container and dry bulk vessels (Table 1). Thus, their demolition starts earlier (see the blue line in Figure 1). At the same time, smaller ships tend to have a higher live expectancy, so it can be expected that by 2050 there will be a higher share of the currently existing smaller ships still in service than of the currently existing larger ships (Figure 1).

Figure 2: Distribution of the expected remaining share of the currently existing fleet, beginning of year, by vessel type

If recent scrapping patterns persist, it can be expected that by the end of 2030 (i.e. beginning of 2031), 17% of the current dry bulk carrier fleet will have been demolished, while 83% will still be in service. For container ships, 43% can be expected to be scrapped and only 57% of the currently existing container fleet will still be in service end of 2030 (beginning of 2031 in the chart). The ships that will replace the withdrawn capacity during the next decade are likely to be still burning traditional fuels.

These figures highlight the urgency in developing new technologies as soon as possible, to avoid that the fleet renewal of the next years will include too many traditionally fuelled ships which will then still service global trade for decades to come.

Our analysis is a purely statistical extrapolation. For many ships, the actual scrapping age will be different than what would be expected from past behaviour. Technological developments, changes in the geography of trade, energy prices, alternative fuel options, IMO and other relevant regulations affecting ship operations, and scrapping conditions will all have a bearing on the future decisions of ship owners on when to sell their ships for demolition.

Some measures to reduce CO2 emissions, categorized as “short-term measures” in IMO’s Initial Strategy on reduction of GHG emissions – such as speed limits – can have an immediate positive impact on the industry’s carbon footprint. They may, however, also lead to fuel savings and higher freight rates, which in turn may reduce the incentive for ship owners to replace the existing fleet with newer vessels. A key aspect will be the cost of emitting CO2, including a potential carbon levy, vis-à-vis the costs of investments into new technologies and alternative fuels. The higher the costs of emitting CO2 and the lower the costs of new technologies, the earlier the currently existing fleet can be expected to be replaced with ships that help the industry to achieve its objective of “getting to zero”. Uncertainty about future regulations, continued overcapacity and pessimistic economic forecasts have contributed to lower new-vessel orders. For example, “[c]ontainership contracting activity in 2019 was limited, with orders placed for 97 vessels of 0.79m TEU, down 37% y-o-y in capacity terms” (Clarksons Container Intelligence Monthly, January 2020).

Our initial extrapolation presented above should be expanded and updated, including data on deliveries over more recent months and the current orderbook. In this article we aimed at presenting initial basic data, which highlights the urgency with which new technologies will need to be developed and deployed if the shipping industry really wants to replace scrapped tonnage with zero-emission ships to achieve its 2050 target.

Jan Hoffmann, Chief, Trade Logistics Branch, Division on Technology and Logistics. Jan.Hoffmann@UN.org

Note: This article reports on ongoing work for a contribution to a forthcoming joint research paper on “Scrapping Probabilities and Committed CO2 Emissions of the International Ship Fleet”, with Maximilian Held, Boris Stolz, Jan Hoffmann, Gil Georges, Michele Bolla, and Konstantinos Boulouchos of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.