- Debt, delusion and policy drift likely to impact economic effects of health crisis.

- Downside scenario sees a $2 trillion shortfall in global income with a $220 billion hit to developing countries.

- Coordinated policymaking is needed to ensure localized incidents do not impact global markets.

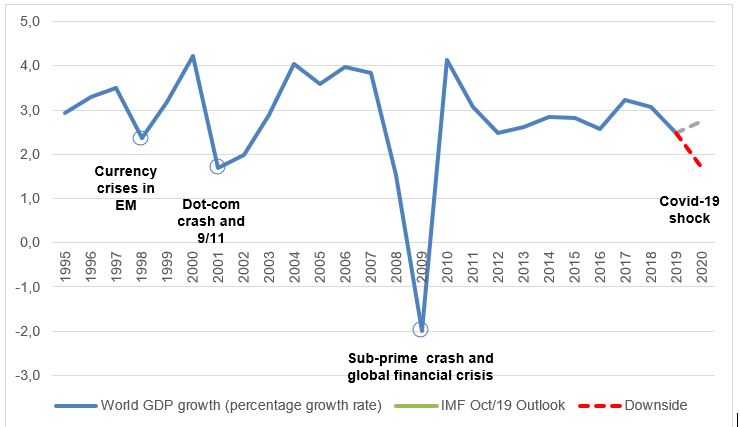

The spread of the coronavirus is first and foremost a public health emergency, but it is also, a significant economic threat. The so-called “Covid-19” shock will cause a recession in some countries and depress global annual growth this year to below 2.5 per cent, the recessionary threshold for the world economy.

Even if the worst is avoided, the hit to global income, compared with what forecasters had been projecting for 2020 will be capped at around the trillion-dollar mark. But could it be worse? Published today, a new UNCTAD analysis suggests why this may be the case.

Losses of consumer and investor confidence are the most immediate signs of spreading contagion, the analysis suggests.

However, a combination of asset price deflation, weaker aggregate demand, heightened debt distress and a worsening income distribution could trigger a more vicious downward spiral. Widespread insolvency and possibly another “Minsky moment”, a sudden, big collapse of asset values which would mark the end of the growth phase of this cycle cannot be ruled out.

“Back in September we were anxiously scanning the horizon for possible shocks given the financial fragilities left unaddressed since the 2008 crisis and the persistent weakness in demand,” said UNCTAD’s director of Globalization and Development Strategies, Richard Kozul-Wright.

“No one saw this coming – but the bigger story is a decade of debt, delusion and policy drift.”

The Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s offers some parallels with the current situation, but that crisis occurred before China gave the region a much bigger global economic footprint and when the advanced economies were in reasonably good economic shape.

This is not the case today.

Public and private aggregate debt levels in many developing countries already are at elevated, and in several cases acute, distress levels.

While the recent explosion of corporate debt, much of it of low credit quality, poses the most immediate danger in advanced economies, developing countries face a range of fast deepening financial and debt vulnerabilities that do not bode well for their ability to withstand another external shock, Mr. Kozul-Wright said.

China also has become a crucial source of longer-term borrowing for developing countries and if its lending conditions tighten with the slowdown, those with strongest financial links to China might be amongst the slowest to recover from the economic impact of the Covid-19 crisis.

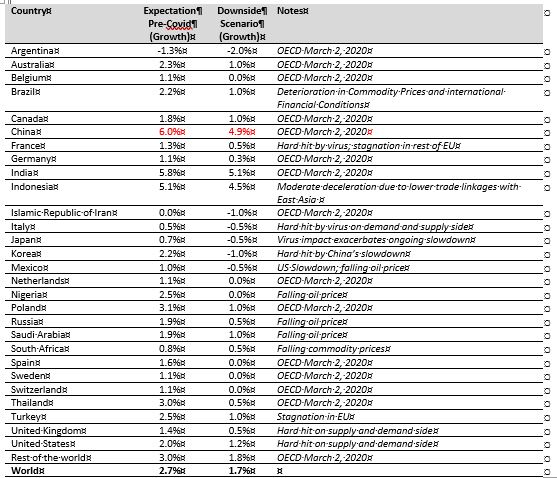

A preliminary downside scenario sees a $2 trillion shortfall in global income with a $220bn hit to developing countries (excluding China). The most badly affected economies in this scenario will be oil-exporting countries, but also other commodity exporters, which stand to lose more than one percentage point of growth, as well as those with strong trade linkages to the initially shocked economies.

Growth decelerations between 0.7 and 0.9 per cent are likely to occur in countries such as Canada, Mexico and the Central American region, in the Americas; countries deeply inserted in the global value chains of East and South Asia, and countries in the immediacy of the European Union.

The analysis points out that a persistent belief in the soundness of economic fundamentals and a self-correcting world economy continues to hamper policy thinking in the advanced economies.

“This will stymie the bolder policy interventions needed to prevent the threat of a more serious crisis and increases the chances that recurrent shocks will cause serious economic damage in the future,” Mr. Kozul-Wright added.

Central Banks are not in a position solve this crisis alone and an appropriate macroeconomic policy response will need aggressive fiscal spending with significant public investment, including into the care economy, and targeted welfare support for adversely affected workers, businesses and communities, the analysis argues. International coordination of these programmes will be required.

Ultimately, says Mr. Kozul-Wright, a series of dedicated policy responses and institutional reforms are needed to prevent a localized health scare in a food market in Central China from turning in to a global economic meltdown.

Figure 1. Global GDP Growth, 1995-2020

Source: UNCTAD calculations based on IMF, WEO, October, 2019