By Paul Akiwumi, Director for Africa and Least Developed Countries, UNCTAD

© UNIDO | A hydropower plant in Shiwang’andu, Zambia.

Zambia aspires to become a prosperous middle-income country by 2030 despite development challenges and socioeconomic vulnerability.

Building on its recent socioeconomic performance and determination to achieve accelerated and inclusive growth, Zambia met the criteria for least developed country (LDC) graduation for the first time in 2021.

Despite impressive strides, the country faces a double set of development challenges. First, heavy dependence on extractive sectors renders the economy highly vulnerable to external shocks. Second, Zambia faces the enduring challenges of being a landlocked developing country (LLDC).

These compounding factors pose significant challenges for creating decent jobs and reducing poverty. While not insurmountable, they call for a new generation of development policies centred on the fostering of economy-wide productive capacities and structural economic transformation.

Development challenges

The Zambian economy remains significantly dependent on the mining and export of copper, with ores and metals accounting for 71% of exports in 2019. This has left the economy vulnerable to commodity price fluctuations.

Meanwhile, the agricultural sector continues to be characterized by smallholder farmers and by low levels of productivity and limited linkages with other value-added sectors. In 2019, agriculture accounted for nearly 50% of employment but only 3% of gross domestic product (GDP), down from 9% in 2010.

Due to Zambia’s premature de-industrialization, the largest shares of GDP and employment originate from services - characterized by informality and low-skilled jobs. Meanwhile, manufacturing value-added (MVA) continues to decline, even faster than median falls in manufacturing seen in LDCs, LLDCs and across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Surprisingly, this occurs even though Zambia has important manufacturing sub-sectors, such as wood and paper products, chemicals, rubber and plastics, and food, beverages and tobacco.

A weak energy sector, dominated by hydropower infrastructure, continues to hold back industrial development. The mining sector alone accounts for 50% of domestic energy demand. In addition, the country struggles to provide sufficient electricity access, especially in rural areas. In 2019, only 43% of Zambians had access to electricity, hindering progress in ICT and e-commerce development.

As an LLDC, Zambia also faces high transportation costs and weak export competitiveness, which are exacerbated by a limited transportation network and inefficient trade logistics. Moreover, there is a high prevalence of informal micro, small and medium-sized enterprises – up to 72% of workers — and underemployment, especially among young people.

Need for productive capacities’ development

Weak and vulnerable growth and a lack of productive capacities have had a detrimental impact on Zambia’s poverty reduction efforts. In 2015, 54% of the population was living below the national poverty line, 77% of whom lived in rural areas. Extreme poverty increased from 43% in 1998 to a high of 66% in 2010, before declining to 59% in 2015.

Moreover, Zambia’s economy was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, real GDP contracted by 2.8%. Tourism was decimated due to severe international travel restrictions.

As the international price of copper fell sharply in 2020, Zambia experienced a significant loss in export revenue, precipitating a default on external debt in November 2020. The country is now classified as a highly indebted country, with the national debt surpassing 120% of GDP.

As a result, Zambia has been reclassified by the World Bank as a low-income country. While its real GDP recovered to 3.6% growth in 2021 on the back of a rebound in copper prices and production, this was insufficient to revive per capita income.

Although the reclassification may not have an impact on Zambia’s graduation from the LDC category, the country’s recent performance, is worrying. Should Zambia wish to graduate with momentum, the country will need to focus action and coordinate policies to build its domestic productive capacities.

Tools to monitor progress and identify action areas

To design adequate policy interventions to build productive capacities, it is of paramount importance to assess existing sectoral gaps. To this end, UNCTAD prepares national productive capacities gap assessments (NPCGAs).

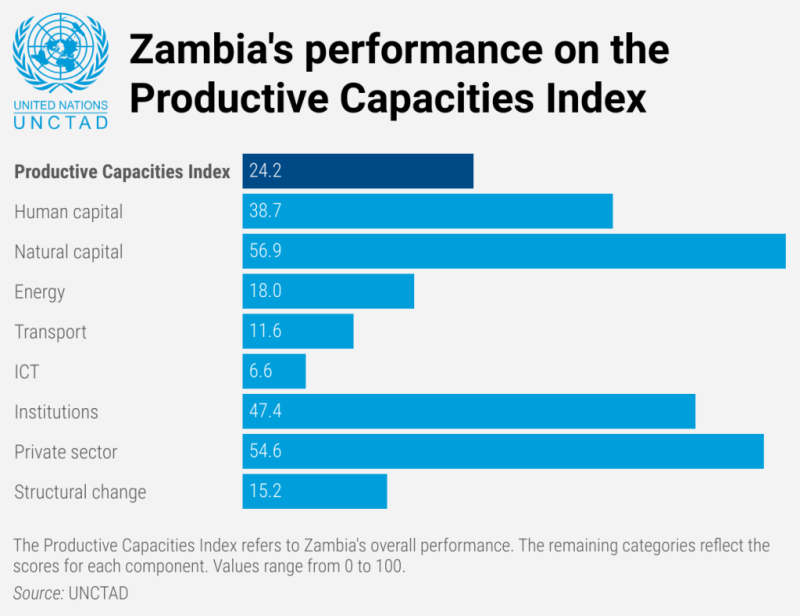

The Productive Capacities Index (PCI) provides the statistical foundations for NPCGA analyses, relying on eight categories to measure different components of productive capacities – natural capital, human capital, private sector, transport, energy, ICT, institutions and structural change.

It identifies comparative advantages and key binding constraints to socioeconomic development and recommends a series of pragmatic and forward-looking policy actions.

The NPCGA of Zambia reveals that the country lags developing countries on many measures of the PCI. Nevertheless, the country’s overall performance is slightly better than the average for all LDCs, while it remains lower than Africa’s regional average.

Zambia’s weak performance on the energy (electricity), ICT, private sector and transport components is particularly worrying. Private sector development remains a challenge despite relatively well-functioning institutions, whereas natural capital has declined below the regional average for Africa.

Ingredients for success

There are, however, reasons for optimism, building on Zambia’s Vision 2030, which aspires to “transform the economy to become strong, dynamic and self-sustaining, which propels the country to a prosperous middle-income nation by 2030”.

Zambia’s Eighth National Development Plan signals the importance of industrialization and economic diversification and emphasizes the need for a competitive private sector. Addressing these priorities will be important to advance towards achieving the country’s economic transformation and job creation targets.

At the same time, the plan underlines the role of education and skills development, as well as financing and policy coordination, taking a more holistic and comprehensive approach to development policy.

Moreover, as global demand for Zambia’s natural resources such as copper and other minerals continue to grow, rents from mineral exports should be used efficiently.

Effective management of its national debt profile could lower debt servicing costs, reduce the risk of debt distress and align debt management with national development objectives. Fiscal discipline needs to be maintained to ensure the success of macroeconomic policies and diversification efforts.

Prioritizing productive capacities is critical to achieving structural economic transformation, which, if conducted in an inclusive and sustainable manner, will accelerate growth, facilitate Zambia’s participation in the global economy and ultimately lead to more effective poverty reduction.

The country must also focus on strengthening human capital and implementing policies to boost employment in new, dynamic sectors and enhance labour productivity. Attention must be on building a robust manufacturing sector.

Stress should be placed on technological upgrading and the development of conducive legal and policy frameworks and linkages with existing manufacturing.

Furthermore, promoting a mix of renewable energy sources to improve electricity supply, in particular in rural areas, will be critical for industrialization. Private sector development should be a priority, as the key driver of structural change.

Domestic and foreign direct investment must focus on transport infrastructure, technology, know-how and innovation. Continuous strengthening of institutions will also facilitate the process.

Way forward

Looking ahead, Zambia must address its developmental vulnerabilities head on, with adequate long-term policy interventions.

To support the country’s efforts, this week, UNCTAD organized technical and policy-level capacity-building workshops in Lusaka to assist the government to place the fostering of productive capacities and structural economic transformation at the centre of domestic policies and strategies and build socioeconomic resilience to external shocks.