By Rachid Bouhia, UNCTAD Economist

Climate catastrophes increase the vulnerability of developing countries. © Anna

The pandemic has exposed and exacerbated alarming debt levels in developing countries. By the time COVID-19 emerged, public debt in developing countries had increased steadily since 2013, in a context of more recurrent external shocks and rising fragilities in their debt positions, including those related to climate change.

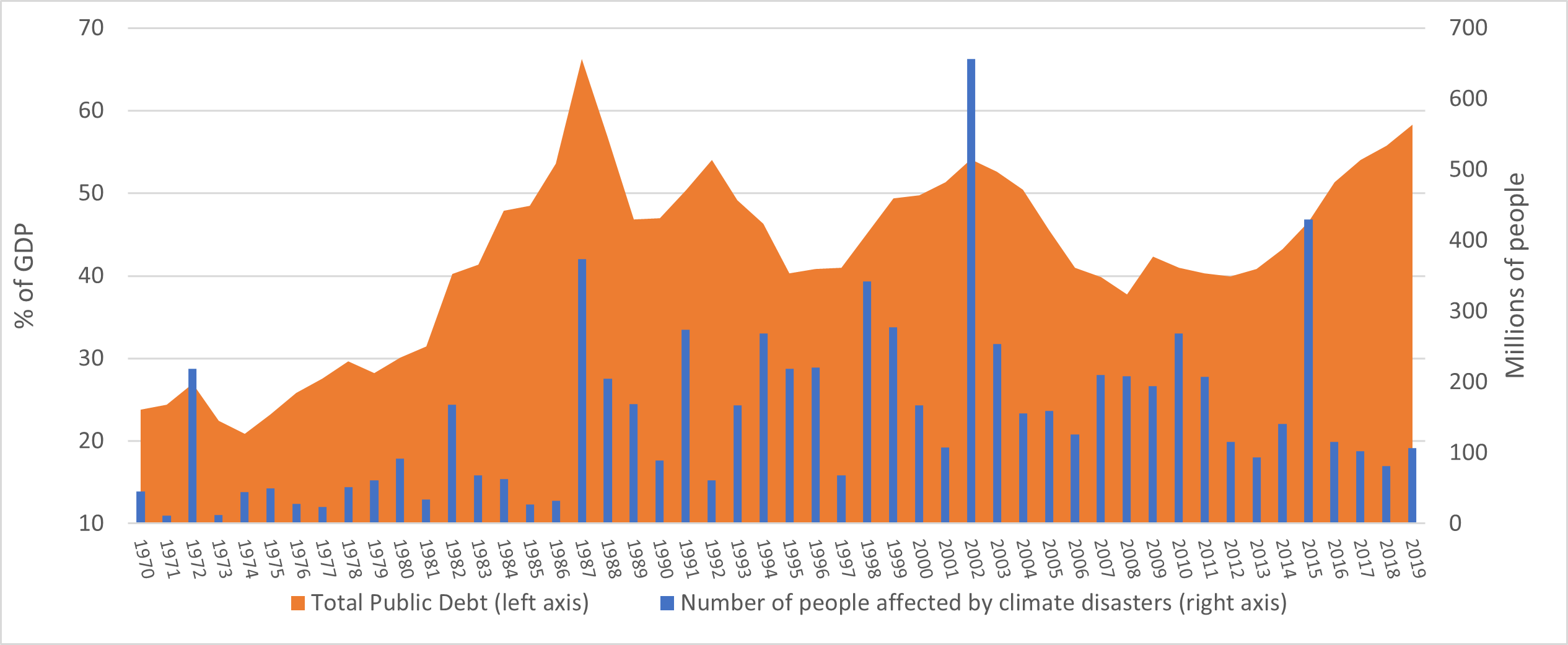

By the end of 2019, their total public debt – external and domestic – stood at 59% of combined GDP, the second-highest level on record (see the figure below). On a more positive note, there had also been a notable increase in the diversity and quantity of climate-related financial instruments at the national and regional levels.

Information on the nature and scale of these initiatives is today critical to our understanding of – and policy response to – debt statistics.

Total public debt as a share of GDP in developing countries and number of people affected by climate disasters, 1970 – 2019

Source: Author’s calculations based on the EM-DAT International Disaster Database and IMF Global Debt Database

Several initiatives launched by the international community have sought to support developing countries fight the COVID-19 pandemic and avert sovereign defaults. However, these measures have not shifted away from a conventional framework that grants access to Official Development Assistance, concessional finance and debt relief on the basis of gross national income per capita.

Most middle- and high-income countries are therefore not eligible to receive concessional finance from multilateral financial institutions. Moreover, evidence suggests that as low-income countries approach or join the middle-income countries’ group, donor governments scale down their development co-operation programmes.

Pressing request by developing countries

Meanwhile, many developing countries, especially those in the growing contingent of countries at the forefront of climate challenges – including small island developing states (SIDS) and members of the Vulnerable Twenty Group (V20) – have requested that environmental vulnerability be taken into consideration when it comes to accessing concessional finance. This request has become even more pressing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as many of them have experienced debt distress.

The main solution explored so far has been to use environmental vulnerability indices, such as the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI). While use of the MVI – which still lacks universal agreement – could be a first step towards better resource allocation across international financial institutions, such environmental indices do not grasp all the economic and financial repercussions of climate change.

They measure risk – to what extent countries are exposed to climate change, but not the actual effects of climate disasters. Another weakness of such indices is that they do not provide information on how well shielded a country may be.

Need for a robust vulnerability concept

A robust concept of vulnerability should encompass both “exposure” and “resilience” dimensions. To this end, environmental indices should be supplemented with climate-related debt statistics.

As the fight against climate change is almost totally financed through debt, such an “expenditure” approach would provide comprehensive insights on both environmental exposure and resilience.

Particularly needed are indicators showing the share of the debt burden intended to combat climate change in total public debt, broken down by ownership (external versus domestic) and currency composition (foreign versus local).

Unfortunately, current official debt statistics do not permit the computation of such indicators – not only because climate-related data is not reported but also because these statistics are based on an outdated paradigm that assumes a perfect concordance between ownership and currency composition of public debt. These have increasingly diverged over the last decades despite the continuing burden of the “original sin”.

Countries highly exposed to climate change would naturally exhibit higher shares of climate-related debt. Erratic trajectories of these indicators would additionally reveal their greater difficulty in coping with climate shocks.

Decomposition by currency and ownership would shed light on countries’ ability to mobilize domestic resources against climate change and pave the way for a better assessment of sovereign risks associated with climate disasters.

Indicators on the share of national debt used for climate resilience also serve as a proxy for measuring the intensity of the global fight against climate change.

For developing countries, they would show to public and private creditors alike the extent to which climate change weighs on their public finances, which in turn may improve eligibility for concessional finance and debt-relief programmes as well as improved ratings by credit rating agencies, thereby enabling more and better-quality capital inflows.

How countries can better combat climate change

Countries would be better able to combat climate change through ex ante measures rather than ex post responses to climate catastrophes, the latter generally being less effective and more costly.

Moreover, official creditors who are interested in fostering climate adaption and mitigation would be able to assess progress in this area, ensure that these actions are not detrimental to other facilitators of economic and social development, and be in a better position to promote ex ante approaches by reducing moral hazard.

Private creditors would be better guided in making relevant investments and more inclined to participate in debt restructuring programmes, if need be.

Overall, the indicators proposed here[1] would contribute to reassessing debt sustainability in developing countries to take into account investment requirements arising from the Sustainable Development Goals and the timely implementation of Agenda 2030, in addition to enabling better management of the effects of climate change.

[1] These indicators were presented and discussed in session 2 of the 9th IMF Statistical Forum on “Measuring Climate Change: The Economic and Financial Dimensions”, along with new ways of measuring trade, investment and financial aspects of climate change put forward by UNCTAD.

The article was first published on 7 December on the OECD Development Matters website.