By Paul Akiwumi, Director for Africa and Least Developed Countries, UNCTAD

© Jan Hoffmann - Maseru bridge between South Africa and Lesotho

Landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) face many challenges due to their geographical remoteness from international markets. One of these challenges is high transportation costs due to their dependence on commodity exports.

LLDCs also face constraints to improving the quality of their transport infrastructure to become more competitive in regional and international markets.

UNCTAD developed its Productive Capacities Index (PCI) to support LLDCs and other developing economies to overcome structural challenges, including transport, connectivity and related hurdles.

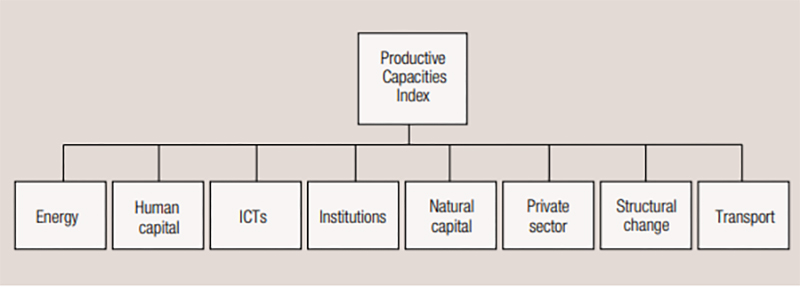

The PCI is an analytical tool designed to support developing countries in identifying their systemic vulnerabilities across different areas of productive capacity illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Productive Capacities Index components

Using the PCI to analyse connectivity gaps across LLDCs

According to studies conducted by UNCTAD and UN-OHRLLS, LLDCs’ relatively higher transport costs are mostly due to their geographical remoteness and high commodity dependence. LLDCs also grapple with infrastructure, connectivity and market access challenges due to their low levels of governance and productive capacities.

The PCI includes a transport component that captures levels of transport connectivity and physical infrastructure in each country or region. Table 1 presents all indicators used to compute the transport component.

Table 1: Indicators encompassed in the transport component of the PCI

|

Transport sub-sector |

Indicator |

Source |

|

Air transport |

Registered carrier departures worldwide per 100 people |

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) |

|

Air transport |

Freight (million ton-km) |

ICAO |

|

Air transport |

Air passengers per capita |

UNCTAD based on data from ICAO |

|

Road transport |

Logarithm of km of roads/100km2 land |

International Road Federation, World Road Statistics |

|

Rail transport |

Logarithm of total km of rail lines per capita |

UNCTAD based on World Development Indicators and web-based archives |

Source: UNCTAD (2021). UNCTAD Productive Capacities Index: Methodological approach and results

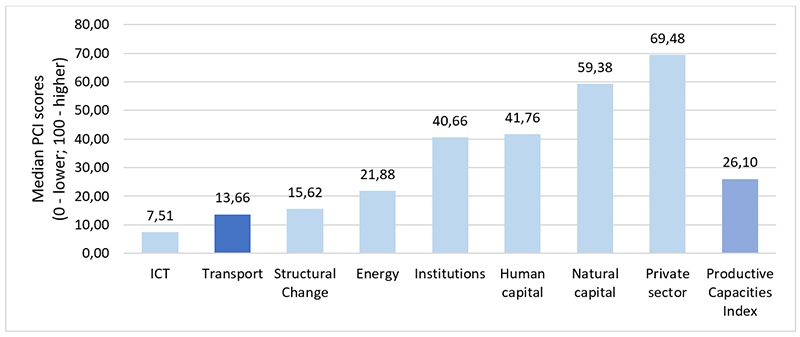

The transport component provides an analytical roadmap for identifying connectivity gaps in LLDCs. One practical way for using the PCI is to compare levels of transport connectivity and physical infrastructure to those in other PCI components such as private sector, human capital, and institutions. Figure 2 presents the PCI scores by component for LLDCs.

In 2018, the median PCI score for LLDCs was 26.1 points. Transport was the PCI component with the second lowest score after the component on information and communications technologies. By contrast, LLDCs performed higher in the private sector and natural capital components.

Figure 2: Median PCI scores by component in LLDCs, 2018

Source: UNCTAD Productive Capacities Index website

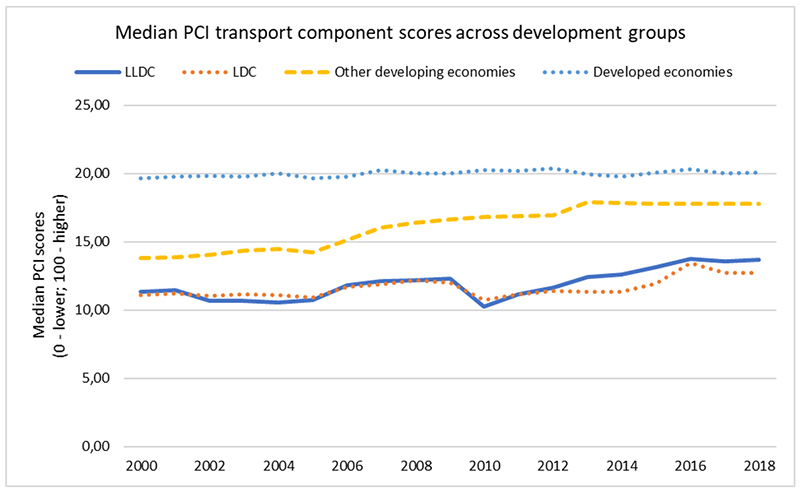

Figure 3 compares the median PCI transport scores of LLDCs with those observed among other country groups.

Figure 3: Median PCI transport component scores across country groups by development status

Source: UNCTAD Productive Capacities Index website

Structurally, LLDCs are at a connectivity disadvantage compared to other economies because they lack direct maritime transport access. Figure 3 confirms this by showing how LLDCs have relatively lower productive capacities in transport.

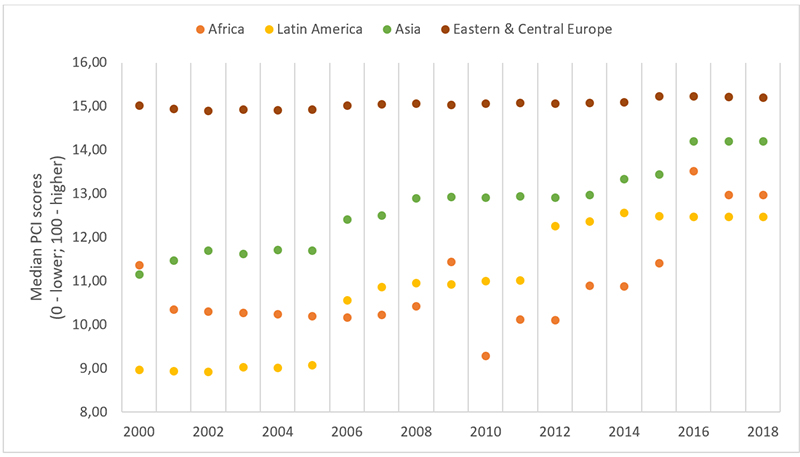

The PCI can help regional development actors to identify specific productive capacity challenges facing LLDCs across geographical regions. Figure 4 shows that LLDCs in Africa and Latin America are catching up in connectivity with their peers in Asia and Eastern and Central Europe.

Figure 4: Median PCI transport component scores in LLDCs by geographical region.

While Africa and Asia account for most of the LLDCs, comparing median PCI scores of the latter across regions enables us to define benchmarks for targeting productive capacity development efforts. Figure 4, for example, identifies the magnitude of connectivity gaps between LLDCs, which would enable policymakers to address the necessary reforms for bridging such gaps.

The challenges facing LLDCs are not limited to transport connectivity. They encompass a range of other issues, including logistics, physical infrastructure and trade facilitation, among others, reflected in gaps observed when analysing other PCI components.

Conclusions

Assessing past and current developments of transport connectivity and physical infrastructure in LLDCs provides a starting point to understand the unique challenges these countries face.

Policymakers and other development actors working on LLDC issues can benefit from the PCI to chart a roadmap for assisting these countries in developing key areas of their productive capacities.

Identifying gaps in connectivity and other productive capacity areas through the PCI can then support resource mobilization and capacity-building that LLDCs need to transform their economies structurally to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.