Article No. 19 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°78 - Second Quarter 2018]

Over the last decades, trade facilitation (i.e. reducing costs and time, as well as improving efficiency and compliance in trade-related procedures) has become a major topic in national trade policies and economic and trade literature.

This is because of increased awareness, by Governments and business, about the relation between (i) easing administrative trade-related domestic procedures and (ii) improved participation in (global, regional and in-country) value chains and competitiveness.

In this context, the positive conclusion of negotiations of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) in 2013, and its entry into force on 22nd February 2017, marked an important milestone. “Trade facilitation” in the TFA context by and large refers to “soft infrastructure” because it focuses on improving trade regulatory and administrative procedures.

This agreement encompasses 36 measures aimed at, simplifying, standardizing and harmonizing trade procedures and documentation related to import, export and transit and making these more transparent. By defining a framework of global administrative and regulatory standards, the TFA has increased transparency and predictability in the way of doing business, increased predictability in terms of delivery and provided a greater sense of trust among trading partners.

Although trade facilitation encompasses principles that are straight forward, they may be technically challenging to implement in practice. This is particularly true for countries with complex administrative environments or those with less capacity to adapt to new technologies, which are still heavily based on paper-based centralized systems.

The objective of this article is presenting two trends related to policy-making in trade and transport facilitation, namely the related increased importance of the hard infrastructure dimension and new governance schemes based on public-private partnerships.

1. Increased awareness of the importance of the hard infrastructure dimension to truly facilitate trade

A trend of parallel facilitation of trade-related procedures (soft infrastructure) and of trade and transport structures and operations (hard infrastructure) can be observed in business practices. Many transport services providers are increasingly “bundling” transport and logistic services to enable optimized operations (i.e. increased efficiency and reduced costs), while at the same time providing value added services to customers. For example, in the maritime transport sector, several maritime liner shipping companies are becoming logistics integrators through IT platforms and vertical integration between carriers and port and dry port terminals can increasingly be observed. (UNCTAD, 2018, -forthcoming- Review of Maritime Transport 2018)

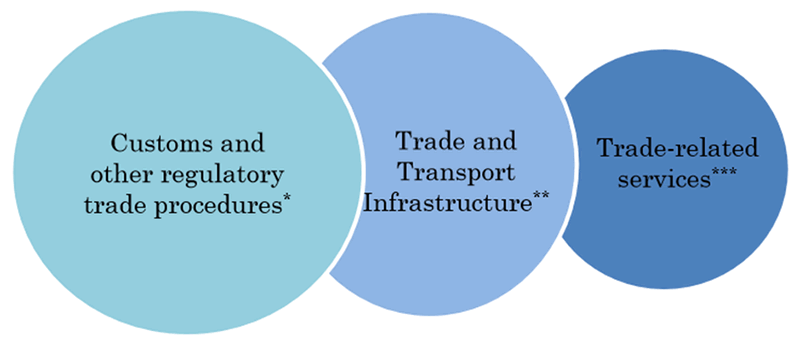

From a policy-making perspective, several databases and tools allow identifying areas for improvement and measuring progress in trade facilitation reforms, as well as comparing performance across countries. These databases and tools recognize three policy areas impacting on trade facilitation. They play an important role in ensuring that goods move swiftly across borders and are key determinants of logistics performance, enabling improvements in the reliability, predictability and efficiency of supply chains.

Figure 1: Trade Facilitation policy areas

Source: ESCAP, OECD, ArtNet and UNNext (2017). “Indicators for Trade Facilitation: A Handbook”

Since the entry into force of the TFA, countries have expanded their policy focus from trade facilitation to trade logistics, encompassing policies to improve “hard infrastructure”. Examples include increased adoption of policies aimed at improving the quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure (such as ports and airport facilities and operations) and at modernizing domestic public management systems with ICT tools, such as the electronic single windows, automated port operations or trade information portals. UNCTAD has a vast experience in these domains supporting TF reforms in developing and transition economies through tools such as the Automated System for Customs Data (ASYCUDA) and Trade Information Portals.

Indeed, ICT infrastructure plays a key role in facilitating trade. The integration of technological tools in customs and tax administration systems (in connection with trade facilitation reforms) enable a more client-oriented approach, speeds up the clearance of goods, reduces time and cost of administrative procedures and ensures traceability in real time. There is still room for improvement in this context, for example through further streamlining documentary requirements and ensuring interoperability of systems.

Another example regarding the increased importance of the hard infrastructure dimension relates to efforts to improve connectivity, for example through corridor development policies at the regional level. Efforts to improve operational, technical and legal aspects of the management of corridors include measures aimed at developing connective infrastructure and elimination of cross-border formalities. The renewed interest in corridor approaches can be linked to the adoption of the TFA, but also to the One Belt, One Road initiative led by China, an initiative that has generated increased interest since 2016. This initiative encompasses more than 900 projects across several sub-regions to connect more than 60 countries, encompassing an important component of hard infrastructure development.

The “hard infrastructure" dimension is particularly important for developing countries. This is because accessing global infrastructure networks and services is closely linked to their ability to access global markets and to improve their position in the global network of value-added trade. For instance, studies[i] based on the UNCTAD connectivity index have demonstrated that trade prospects are significantly affected by how well countries are connected to global liner shipping networks. Furthermore, World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index 2016 highlights that countries with severe logistic constraints also rank lowest in infrastructure-related performance.

2. New governance schemes based on Public-Private Partnerships

Article 23.2 of the TFA stated that each WTO member has the obligation to have a National Trade Facilitation Committee (NTFC) in place “to facilitate both domestic coordination and implementation” of the provisions of the agreement. In addition, as part of Article 2 of the TFA and the terms of reference of NTFCs, the stakeholders represented through the NTFCs should be consulted and be given the opportunity to provide comments to any introduction or amendment of laws and regulations related to the movement, release, and clearance of goods, including goods in transit.

Effective action to improve trade logistics requires coordinated efforts between public and private stakeholders. This is why, in practice, NTFCs are composed of public and private entities involved in trade facilitation but also in trade logistics. Some countries have even decided to have a private sector association chairing or co-chairing the NTFCs. This is the case of the East African Community (EAC) countries, where private sector features prominently leading the NTFCs of the EAC countries. Such practices showcase political support to have trade logistics practitioners providing inputs in the crafting of trade facilitation policy. NTFCs enable exchanging views and discussing about trade issues related to transport, customs, quality control, safety and security. Therefore, the TFA (through NTFCs-related provisions), has provided impetus for new governance schemes based on public-private partnerships.

Another area where new forms of public and private partnerships are taking shape is Customs. In recent years, the risk management approach by Customs has gradually shifted from risk analysis aimed at inspecting and prohibiting many goods categories to a more trade-facilitating approach. This approach entails the possibility to significantly reduce and eliminate controls of goods from trusted operators (also in the broader context of a secure supply chain) and a strengthened (possibly full) control of the trade flows of other traders. “Customs-to-Business” partnerships, for example through standards related to Authorized Economic Operators are a key pillar contained in instruments such as the World Customs Organization SAFE Framework. These standards recognize common approaches to protection of (i) the trade integrity of (a business partner’s) processes that are related to the transportation, handling and storage of cargo in a secure supply chain and (ii) commercially sensitive business data.

In conclusion

During the last decades, countries have been scaling up trade logistics in domestic trade policies. Governments are currently anchoring policy changes around the implementation of the TFA measures to reduce time and cost of administrative trade procedures and increase predictability for trade, which will benefit participants in Global Value Chains, including MSMEs. Although policies aimed at easing trade-related procedures can undoubtedly make trade more efficient and competitive, a wider trade logistics approach encompassing improvements to “hard infrastructure” and access to logistic services can also play an important role in facilitating trade, particularly in logistically constrained countries.

Improving connectivity and linkages among countries through strong transport networks and freight systems is crucial to promote trade, particularly among regional partners. This means encompassing a broader spectrum of activities along supply chains, to include all processes from the point of entry of cargo to the final destination, encompassing corridor management, ports and airport management, freight forwarding and warehousing activities, as well as security and safety aspects. Policy design in this context implies shifting towards more public-private partnership approaches for policy design and implementation.

[i] Fugazza 2015, World Bank 2013, Fugazza & Hoffmann 2013

For more information about UNCTAD work on trade logistics (= transport infrastructure/services and trade facilitation) visit: http://unctad.org/TLB

For additional information contact Céline Bacrot (celine.bacrot@un.org) or Luisa Rodriguez (luisa.rodriguez@un.org)