Written by Céline Bacrot and Marc-Antoine Faure, Article No. 118 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°101 - First Quarter 2024]

The end of 2023 and the first quarter of 2024 are marked by major disruptions to global maritime trade flows as ships entering the Gulf of Aden and sailing through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal continue to face attacks by Yemen-based Houthis.[1] This new wave of disruption follows the unprecedented global logistics crunch caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout in 2020-2022 and the war in Ukraine since 2022. It also compounds the challenges caused by the reduced ship transits in the Panama Canals resulting from the impact of drought on water levels.

Security threats in the Red Sea have caused a significant redirection of ship arrivals and transits culminating in far-reaching global trade and transport repercussions. Ships across all shipping segments on the Asia-Europe and Asia-Atlantic trade lane have diverted their initial trajectory and started sailing around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. As a result, ships are now travelling longer distances and facing higher operational costs. The rerouting of vessels is creating pressure on the supply side. The 12 days in additional sailing time for a vessel going from Shanghai to Rotterdam[2] are driving up costs and extending delays.

The Red Sea crisis has also impacted African ports and causing congestion as rerouting entails the need for more vessels to call at African ports including for bunkering services. Yet, these ports are not always fully prepared to service additional ship calls and cater to larger vessels.

The disruption in the Red Sea and increased shipping traffic around Africa underscore the need for African countries and ports to scale up ongoing efforts aimed at implementing trade facilitation measures, taking up digitalization and mainstreaming green processes to reduce port congestion and expedite the clearance of goods.

The 2020-2022 upheaval in global logistics and the war in Ukraine have exposed the vulnerability of extended supply chains to disruptions and exposed instances of ill preparedness. The Red Sea crisis and the Panama Canal situation are further emphasizing the need to strengthen transport and trade in the face of disruption and consider how to respond, cope, recover and adapt to the new operating conditions.

In this context, a key question arises: Can African countries leverage the current disruption and explore how, by improving their trade facilitation environment, they can take advantage of the business opportunities that may arise from the additional traffic passing through their ports?

Put differently, could the additional port calls that are currently mostly motivated by bunkering activities stimulate maritime trade? Could the additional port activities motivate additional imports and exports?[3]

In times of crisis, as shown during the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, strengthening the trade facilitation ecosystem is key to keeping trade flowing by reducing port congestion and building the resilience of the border agencies. While, at this stage, it is difficult to measure the long-term impact of the Red Sea crisis on the African economies, it is likely that the unexpected increase in shipping traffic around Africa and higher demand for port and bunkering services will impact port activities and performance. Increased port calls that boost the maritime business could stimulate African economies while at the same time incentivise implementation of trade facilitation measures to expedite the clearance of goods. Examples of such measures include the digitalization of trade procedures and investment in hinterland infrastructure and services along transport and trade corridors.

Short-term Impact and Windfall Effects

The Suez Canal is a global strategic waterway that enables the crossing of 10% of global seaborne trade by volume[4] and 22% of containerized trade flows.[5] The Red Sea shipping crisis is putting considerable strain on international trade, regional stability, and economic recovery, against a backdrop of inflationary pressure and macroeconomic uncertainty.[6]

For African trade, the disruption of the Suez Canal is of significant importance since the European market is the most important trading partner accounting for 26% of all imports in terms of value into African countries, and the first destination market for 26% of all African exports in terms of value.[7] Foreign trade for several East African countries is highly dependent on the Suez Canal. It is estimated that approximately 31% of foreign trade by volume for Djibouti is channelled through the Suez Canal. For Kenya, the share is 15%, and for Tanzania it is 10%. Foreign trade for the Sudan depends the most on the Suez Canal, with about 34% of its trade volume crossing the Canal.[8] As of today, the disruption of the Suez Canal has created shortage of not only perishable but also and normal containers due to the increased cargo delivery time such as such as avocado in East Africa but also tea and coffee supply chains.[9]

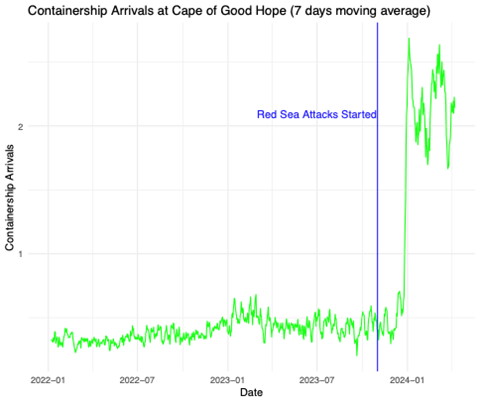

Rerouting vessels around the African continent add about 12 days to the ship journey on a route from Asia to Europe and acts as a negative supply shock equivalent to a roughly 30% increase in transit times. Extended travel distances and transit times are estimated to cut effective global container shipping capacity by around 9%.[10] Indeed, a round trip between India and Europe, for example, takes 56 days and 8 ships. If the journey takes 63 days, an extra ship will be needed.[11]The reduction in vessel transits through the Suez Canal is massive, with a fall of 42% compared with the peak in 2023.[12] The shift from the Gulf of Aden to the Cape of Good Hope is therefore striking: the tonnage of ships entering the Gulf of Aden fell by more than 70% between the first half of December 2023 and the first half of February 2024. Meanwhile, by the first week of March 2024, the gross tonnage of vessels arriving at the Cape of Good Hope has increased by 85% (7-day moving average) compared to the first half of December 2023). The Capes’ containership arrivals by gross tonnage increased by a striking 328% as shown in the figure 1.[13]

Figure 1: Cape of Good Hope Containership Arrivals

Source: UNCTAD chart based on Clarksons Research, March 2024

The cost of shipping doubled on the Shanghai-Rotterdam route and rose by 350% on the Shanghai-Genoa route between 1 December and 1 February[14]. In this context, J.P. Morgan Research emphasises a potential uptick in global core goods inflation by 0.7 percentage points, alongside a 0.3 percentage point increase in overall core inflation during the first half of 2024. In addition to the disrupted trade, the risks of inflation, the diversion of shipping via the Cape of Good Hope has a significant impact on African ports.

The unforeseen rise in demand for port services, in particular fuel requirements, has created significant tension leading to longer journeys due to port congestion in the African region. As Portcast recently pointed out,[15] Durban and Cape Town, for example, are experiencing a sharp increase in activity, which is congesting port capacity. They also point out that deep-water ports – necessary to manage large container ships – such as Mombasa and Dar Es Salaam, lack the resources to cope with the surge in traffic.

Yet, the increased traffic can stimulate shipping, port activity, and boost the revenues of African port authorities. Several ports are capitalising on the rerouting that is taking place. Notably, Clyde and Co highlight the good performance of the port of Maputo, Mozambique.[16] More generally, rerouting through Africa may create new perspectives for the region's ports, which appear, according to Clyde and Co, to be gradually reducing their congestion and better managing this traffic "windfall". Beyond the ports, to the extent that the additional port calls provide new trading opportunities, this situation could lead to greater focus on upscaling digital trade facilitation and increasing infrastructure investment in the hinterland of Africa. While most of the African countries have ratified the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement adopted in 2014, the implementation remains very low and is reflected in a low capacity to adapt to unexpected changes. In addition to expediting the clearance of imports, exports and transit goods, trade facilitation allows for more predictability and adaptability to shocks by modernizing border agencies’ processes with digital solutions and agile and coordinated management systems. As of today, TFA (Trade Facilitation Agreement) implementation rate in many African countries lies between 20% and 79%. Only three countries, Benin, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mozambique, have declared having fully implemented the TFA[17]. The good performance of the Maputo port amid the re-routing of ships via the Cape of Good Hope also reflects the country’s commitment to advancing the trade facilitation agenda.

Could the Red Sea Crisis generate business opportunities for African ports and boost African trade?

The recent surge in demand for bunkering services could generate business opportunities for the Southern African ports, particularly if the disruption in the Red Sea lingers. Given that the challenges faced by the ports around the Cape of Good Hope in November and December have been partially addressed, these ports could potentially leverage the situation to consider future strategic developments to further improve their connectivity. As argued by J. Hoffmann, N. Saeed, and S. Sødal, “improved transport connectivity has a stronger impact on trade in the long run than in the short run showing that traders take some time to adjust their supply chain to the opportunities offered by the shipping networks”.[18] Increased traffic around the African continent could generate more trade flows in the longer run, if the newly created shipping connectivity remains available to importers and exporters. Thus, as long as the level of rerouting and arrivals remain at a high level, maritime business opportunities could emerge in tandem with the increased direct connectivity and the potential spillover effects on the economic development of the coastal regions.

To transform gains derived from the short-term favourable position into medium-term benefits, three critical enabling factors are required, namely human resources, trade facilitation, and regional cooperation. Human resources are essential in implementing and managing trade reforms. Trade facilitation helps increase trade efficiency by streamlining and modernizing trade processes, hence ensuring the smooth flow of goods. The latter is key as it can help to reduce security problems and improve intermodal connectivity in Africa which hosts the largest number of landlocked countries (16). In this context, effective port development requires the parallel development of a harmonized transit systems in road and rail infrastructure to improve the overall connectivity of the transport network and create trade opportunities for transit and land-locked countries.

Moreover, the surge in demand for bunkering services may offer an additional opportunity to advance the maritime decarbonization agenda. Increased maritime connectivity and port activity could increase the pressure towards the green transition in Africa, which would require the provision of alternative fuels and could lead to the development of green shipping corridors. While Morocco is among the signatories of the Clydebank Declaration for Green shipping corridors,[19] Namibia-European Union and South Africa-Europe are featuring among the 44 green corridors identified by the Global Maritime Forum.[20] As underlined in the report The Next Wave: Green Corridors, a broad momentum has been created between the major players along the Asia-Europe route. Many shippers and container operators have set emissions reduction targets.[21] Some African countries have already started transitioning towards green ports and as noted above, two green shipping corridors involve Africa. Notably, South Africa has the natural resources and geography to develop alternative fuels. As South Africa: fueling the future of shipping report shows, in the longer term, this is an opportunity for economic growth, consolidation of value chains and job creation.[22]

Conclusion

The current crisis in the Red Sea has made global maritime transport more dependent on African ports. While the disruption of shipping through the Suez Canal since last November has led to delays in maritime transport in the East African economies, it has also increased sharply the vessel arrivals in African ports, particularly containerships at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. By early March 2024, containership arrivals at South African ports increased by 328% since early December 2023, leading to port congestion in Durban and Cape Town. Port authorities and governments in the region are currently focused on reducing congestion. However, and to fully take advantage of the maritime business and trade growth opportunities arising from additional vessel arrivals, African countries need to invest in implementing trade facilitation measures, improving port operations, enhancing cargo handling capacity, and strengthening coordination among border agencies. Increased shipping connections to African ports not only generate business for ports but also benefit African trade. Regional cooperation, investment in digital trade facilitation and infrastructure, and development of human resources are the main three pillars required to realise this ambition and effectively succeed in this path.

[1] Red Sea, Black Sea and Panama Canal: UNCTAD raises alarm on global trade disruptions. UNCTAD. January 26, 2024.

[2] Seadistance.net. 2024. Sea distance calculator. http://www.shiptrafc.net/2001/05/sea-distances-calculator.html

[3] Hoffmann, J., Saeed, N. & Sødal, S. Liner shipping bilateral connectivity and its impact on South Africa’s bilateral trade flows. Marit Econ Logist 22, 473–499 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-019-00124-8, for example, show that additional direct liner shipping connections, more competition among carriers, and a higher total deployed TEU carrying capacity are associated with higher exports for the cases of South Africa and Namibia.

[4] Based on Clarksons Research data available at https://www.clarksons.com/research/.

[5] Based on MDS Trandmodal data, https://www.mdst.co.uk/.

[6] Precarious passage: Red Sea ship attacks strain supply chains. UNCTAD. February 15, 2024.

[7] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2023/05/26/muddled-priorities-contin…

[8] UNCTAD (2024). Navigating Troubled Water. UNCTAD Rapid Assessment. February.

[9] https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/farm-produce-stuck-due-to…

[10] J.P.Morgan Global Research (2024). What are the impacts of the Red Sea shipping crisis?. February 8th.

[11] UNCTAD (2024). Navigating Troubled Water. UNCTAD Rapid Assessment. February.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Clarksons Research (2024). Red Sea Disruption: Market Impact Tracker. 11 March.

[14] J.P.Morgan Global Research. What are the impacts of the Red Sea shipping crisis?. February 8th, 2024.

[15] Portcast Red Sea Attack Challenges: Port Congestion Updates. January 5, 2024.

[16] Clyde & Co.Navigating Perilous Waters: Houthi Attacks, Global Shipping Turmoil, and Southern Africa’s Bunkering Boom. February, 12, 2024.

[17] See https://www.tfadatabase.org/en/implementation/progress-by-member

[18] Hoffmann, J., Saeed, N. & Sødal, S. Liner shipping bilateral connectivity and its impact on South Africa’s bilateral trade flows. Marit Econ Logist 22, 473–499 (2020)

[19] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cop-26-clydebank-declaration…

[20] See https://cms.globalmaritimeforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Global-M….

[21] The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard classifies a company’s GHG emissions into three ‘scopes’. Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources. Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy. Scope 3 emissions are all indirect emissions (not included in scope 2) that occur in the value chain of the reporting company, including both upstream and downstream emissions. https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards_supporting/FAQ.pdf

[22] Global Maritime Forum, South Africa: fuelling the future of shipping. 2021.