Article No. 46 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°85 - First Quarter 2020]

For the past five years, delegations from Fiji, the Marshall Islands, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Kiribati and Tonga to the IMO have been calling for increased reduction in international shipping emissions. Their sustained, consistent pressure since 2015 is widely credited as a catalyst that has forced shipping to address its role as a major global Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emitter and led to IMO setting firm targets in 2018 to begin decarbonising the industry. Although these targets are not high enough to stay under 1.5 degrees, they are a major step forward.

Five years ago, the discussions on this matter were very much a backroom affair, held outside the major global debates on climate change. Today, shipping emissions are a high-ticket item, at the forefront of the UN Secretary-General’s Climate Change Summit last year. They will be a centrepiece of the UN Oceans Summit in Lisbon in June this year. The Pacific can be justifiably proud of the work of its diplomats and delegations in driving this agenda.

Why is shipping important to climate change?

International shipping is a behemoth of a global industry. As real enablers of world trade, ships move 90% by volume and 80% by value of all goods in the world. No other form of transport can move the huge volumes of raw resources and finished products that keep the global economies gears grinding.

Ships are often the most energy efficient transport available, compared with trucks and planes. It’s an industry of big numbers: ships can cost $100’s of millions to buy; a large oil tanker might carry a $100 million worth of crude and some container ships can carry more than 20,000 containers at a time.

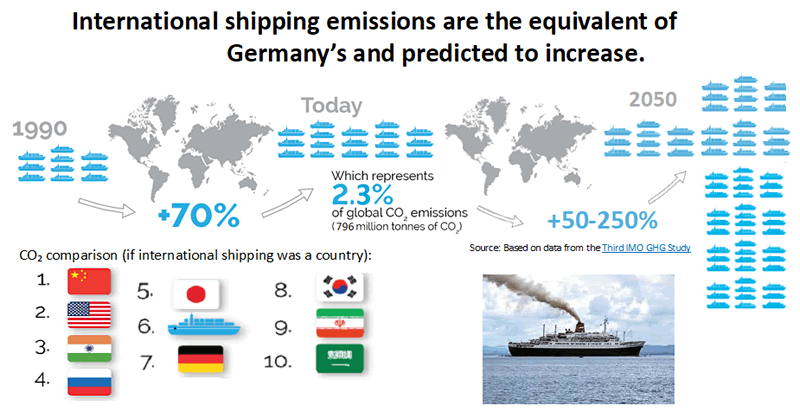

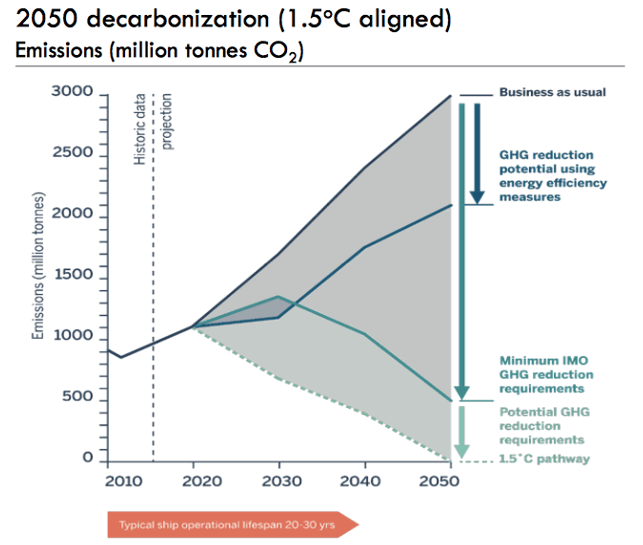

So why the concern? Because big ships burn large quantities of dirty fuels and shipping emissions of GHG are high and increasing. Because global trade is forecast to grow, so shipping must also expand. If shipping was a country, it would be an emitter of the same size as Germany. If we do not change shipping’s carbon footprint now, by 2050 it could emit as much as the continent of Europe (see figure 1). Ships are expensive assets and have a working life of 20-30 years or more. This means we must make the decisions about how to change shipping to non-carbon fuels and technologies now, not in 2030 or 2050. It will be too late then.

Shipping, and its cousin aviation, are international industries, servicing across and beyond national borders. So, it was left out of the Kyoto Protocol and from the Paris Agreement on climate change, the main legal instruments regulating national emissions. Instead, shipping is regulated at the global level by another UN Agency, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). In the build-up to the Paris Agreement, shipping stayed out the limelight of the global debates on climate change. This is because it tends to be an 'out sight, out of mind' industry for most people and the IMO has a heavy industry presence and influence. Previous IMO discussions on regulating ship emissions using market-based measures, such as carbon or fuel taxes, had created large divisions between the member states and were abandoned a decade ago.

Why are Pacific Islands playing such a critical role in the IMO current debates?

One of the leading architects of the Paris Agreement was the then Marshall Islands Foreign Minister Tony de Brum. The Marshall Islands is also host to the 2nd largest ship registry in the world and this makes it a superpower in shipping. In 2015 Minister de Brum led a Pacific delegation to the IMO calling for reductions commensurate with 1.5 degrees (see figure 2)

Since then, we have been joined by other high ambition countries, including many from Europe, New Zealand and Canada. Working closely with other UN partners such as UNCTAD we are reaching out to other SIDS and climate vulnerable countries. While our shipping interests are quite different to those of Europe and large developed trading nations, we are proving that we all face a common threat in this climate crisis and that mature, measured debate is still the best path to durable solutions. The Shipping High Ambition Coalition (SHAC) we have forged since 2015 provides a space for this to occur. It is a unique approach.

Collectively, the IMO member states must now agree a managed step change from fuel oil powered to non-carbon ships. That will be no small feat, given that some of the major actors do not see the climate crisis with same the urgency as the Pacific. Some do not admit to seeing it at all.

Small and poor countries, the most vulnerable to climate change, do not usually have a loud voice in IMO. They are not normally associated with the major shipping powerhouses or the shipping interests of large states. It is very expensive to maintain delegations to the IMO in London. But with technical support from our international university partners and funding support from New Zealand, the United Kingdom and, more recently, the European Union we have been able to sustain an increasing Pacific voice to the unique concerns and interests of Small Islands Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs). As our small delegations shuttle back and forth to London it sometimes feels like a total David and Goliath struggle. However, there is also immense pride in watching our officers and diplomats grow in confidence and stature. They are certainly earning global respect.

Now that the IMO has set its initial target of at least 50% overall emissions reduction by 2050, the real debates over what measures to employ and how to enforce them are coming to the fore. These are highly technical in nature and will become increasingly so. There is a lot at stake. Our latest science is that an investment of at least $1 trillion is needed to transition global shipping to new generation green fuels – most likely ammonia, hydrogen, and biofuels. Industry leaders are moving quickly to position themselves to benefit from this massive investment opportunity.

This context also raises important questions for our small islands: will we also benefit, or will we will be left behind and increasingly penalised? Here in the Pacific we have some of the highest shipping costs in the world. In addition, we are increasingly dependent on shipping for our connection to the rest of the globe, our transport lines are long, thin, expensive and vulnerable. We are ‘the maritime continent’. Our work of the past five years has demonstrated that, with the right support, a Pacific voice can be heard despite our small stature. But a lot more work lies ahead if the interests of our islands in this huge international debate are to be protected.

Dr Peter Nuttall is the scientific and technical advisor at the Micronesian Center for Sustainable Transport (MCST). The MCST is a joint initiative of the Republic of the Marshall Islands and the University of the South Pacific. He has been part of the team of scientists and universities providing research and technical support to Pacific Island members working with other high ambition countries in IMO decarbonization debates.

Contact: peter.nuttall@usp.ac.fj