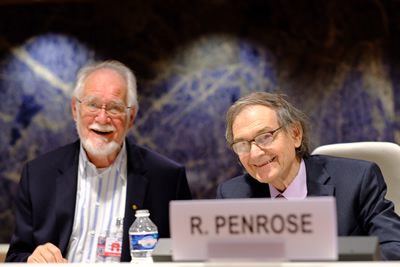

Though we should applaud technological advances like artificial intelligence, we must remember that human intelligence is behind our new devices, and that whether innovation leads to a better world depends on us, renowned mathematician Sir Roger Penrose and Nobel Prize-winning chemist Jacques Dubochet told the opening session of the UN Commission on Science and Technology for Development.

The commission is meeting this week from 14 to 18 May at the Palais des Nations on the banks of Switzerland’s Lake Geneva to discuss how countries can ensure that scientific research and frontier technologies lead to better lives for all.

For one hour, government ministers and civil society representatives in attendance could tap into the great minds of Mr. Penrose, an Oxford University professor who has made significant impact in the world of mathematics, quantum mechanics and physics, and the Swiss academic Mr. Dubochet, whose work has often been about creating a link between science and social issues.

Technological innovation is making the unthinkable possible every day, the event’s moderator, Didi Akinyelure of the BBC, said, citing the example of hydroponic systems and LED technology that allow Londoners to grow salad in an abandoned bomb shelter some 30 metres below the city.

But the question that remains, she said, is whether we’re prepared for such innovation.

For Mr. Dubochet, the scientific community must give more importance to how knowledge and innovation are used, not just to how they're produced.

“We scientists are good at producing knowledge,” he said. “And, indeed, we produce a lot of knowledge which is transformative for the world – artificial Intelligence is one of those.”

“But, do we use it for the best of mankind?” he asked.

Unfortunately, “this is clearly not the case,” he said, citing the example of research in the scientific field of genetics.

“I think this is a typical case where progress is remarkable – the knowledge is improving very rapidly – but where we’re not prepared to control it, so that it is used for the best,” he said.

“It will be used for very great things. That’s clear. But it could also be used for very nasty things.”

Remain in control of your devices

So who’s responsible for anticipating the impact of science and technology on people and society?

“At the beginning, scientists are responsible,” Mr. Dubochet said. “They must feel this responsibility. It’s not enough to just produce knowledge,” he said, adding that scientists must remember they are citizens first.

“I think for a lot of these new technologies, it’s not possible to just leave the scientist alone,” he said, suggesting that the precautionary principle should be applied “in all these areas of science where the possibility of danger is open.”

Similarly, Mr. Penrose said that for innovation to lead to the right kind of progress, we must remain in control of our devices.

Though digital technologies seem to have taken over, often performing many tasks far better than humans, our devices don’t understand what they’re doing and get their intelligence from humans, he said.

“And I want to emphasize that we have to be not overawed by the success of these technologies, because these technologies are a partial story,” he said, urging for a more “symbiotic relationship” between humans and their devices.

We need computers to cope with the huge amount of information out there, he said, but we need humans to design and understand them, and to teach others how to use them.

“And I think this is an important message,” he said. “We have to maintain our control over the devices. We have to show their limitations. We have to point out the dangers.”

He added: “I think perhaps my role here is, I hope, to point out where there are dangers rather than celebrate the successes. And I think the successes are great. But nevertheless, we have to understand this in the broader context.”

And according to both acclaimed scientists, UN meetings like the Commission on Science and Technology for Development are needed to place innovation in the broader context of development and human wellbeing.

Mr. Dubochet said: “When I got this Nobel Prize in Stockholm, I expressed the view that everything that deals with medicine should be under the control of the World Health Organization. This is right for everything which has to deal with medicine. It should be the same for any kind of knowledge – computer, of course.”

Mr. Penrose added: “I think it’s fundamental that the United Nations rather than any particular country should be concerned with these issues.”

The event was livestreamed on Facebook (starts at around 3 minutes).