Written by Mena Hassan and Tarig Ahmed, Article No. 123 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°103 - Third Quarter 2024]

Why and how countries acceding to the WTO can leverage on the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is the main global international organization regulating the rules of trade between nations and it is open to states or customs territories with full autonomy over their external commercial relations. To join the WTO, a government should bring its economic and trade policies in line with WTO rules and principles and negotiate with existing WTO members about access to its domestic markets for goods and services. The accession process which takes place under Article XII of the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the WTO begins when WTO members accept an application and establish a Working Party. It concludes when WTO members and the acceding government accept negotiated terms of accession. [1]

Since the establishment of the WTO in 1995 [2], there have been 38 accessions, with the most recent being Comoros and Timor-Leste, two Least Developed Countries (LDCs), who joined the WTO on 21 August and 30 August, 2024 respectively. This was a significant moment for the multilateral trading system as it marked the first expansion of the membership since 2016, the longest gap in WTO history. For the recently acceded members, known as Article XII Members, the overall average time for accessions is around 10.5 years while LDC accessions took an average of almost 13 years. [3]

Currently, there are 22 governments negotiating accession to the WTO. Their overall average time in the accession process is 19.5 years. Accession to the WTO promotes economic growth by enhancing trade, stabilizing trade revenues, and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) through a predictable trade policy environment. Acceding governments commit to comprehensive economic and trade reforms, including lowering tariffs and non-tariff barriers, regulating state-owned enterprises, safeguarding intellectual property rights, and setting up independent judicial systems. These changes foster a more competitive and transparent economic landscape, driving deeper development and integration into the global economy.

While it is generally accepted that the benefits from WTO membership outweigh staying outside the multilateral trading system, acceding governments face many challenges in their bid to join the organization. These include inter alia difficulties in sustaining strong political momentum as well as maintaining the negotiating team for the duration of the process which takes years and at times decades; limited understanding of the scope and complexity of obligations associated with WTO accession and related impact on the country's economic development; lack of experience and skills in trade related negotiations; and limited analytical capacity to support trade analysis and impact assessment studies. It is therefore crucial that accession processes are accompanied with the provision of technical assistance and capacity building, especially from partner organizations like UNCTAD but also ITC, the World Bank and regional development partners.

The WTO TFA

The Agreement on Trade Facilitation (TFA) is the first multilateral agreement reached since the establishment of the WTO in 1995. The TFA entered into force on 22 February 2017, after almost ten years of negotiations and obtaining two-thirds acceptance from its (at the time)164 Members. Unlike in previous Uruguay Round agreements[4], or even GATT agreements, the TFA is a multilateral agreement that has been designed in a way that provides for the interests of all WTO Members, depending on their level of development. This is largely thanks to the 2004 Annex D of the July Package, which set an unprecedented and unique negotiating mandate. The fact that commitments are tailor made for each developing country and LDC, coupled with the clear linkage between implementation and capacity, is a key premise for the success of this Agreement.

The TFA is based on GATT Articles V, VIII and X of 1994. Section I of the TFA comprises 12 Articles, sub-divided in approximately 36 trade facilitation measures. TFA Articles 1-5 are transparency-related measures. TFA Articles 6-10 prescribe certain disciplines regarding fees and formalities connected to importation and exportation, as well as penalty disciplines. TFA Article 11 focuses on freedom of transit in order not to discriminate against goods in transit which is especially important for traders from land-locked countries. Lastly, Article 12 has set out provisions for customs cooperation.

Section II of the TFA sets out the Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) provisions for developing countries and LDCs. Most notably are the categories of commitments. Based on Article 14 of the TFA, not only will each developing and LDC member have their individual tailor-made implementation schedules, but these will be divided into three categories of commitments, determined on an countries own assessment: category A includes measures which are already implemented upon entry into force or accession; category B includes measures which require longer time to implement; and category C includes measures which require longer time and technical and/or financial assistance and capacity building. For category C the obligation to implement is dependent on receiving the required assistance.

Institutional arrangements and final provisions of the TFA are prescribed in Section III. The main provision relates to the establishment of a WTO Committee on Trade Facilitation and a National Committee on Trade Facilitation (NTFC).

Benefits of WTO membership and the implementation of the TFA

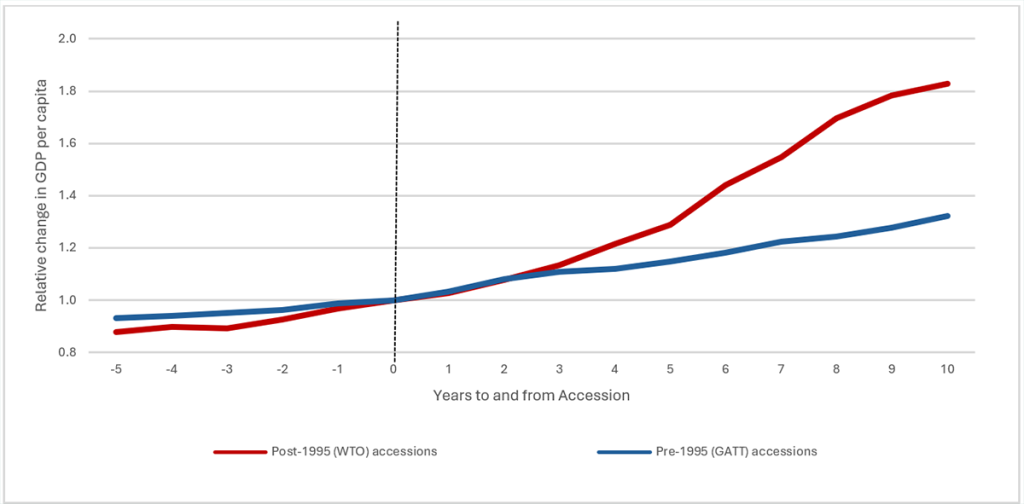

Based on WTO research, economies that acceded to the WTO under Article XII experienced notable growth compared to those that acceded during GATT, without comprehensive commitments (i.e. pre-1995). Figure 1 compares GDP per capita growth of economies that acceded (i) pre-1995 and (ii) post-1995 (under WTO, with strong commitments).

Figure 1: Acceded members GDP growth relative to year of accession

Source: WTO Secretariat.

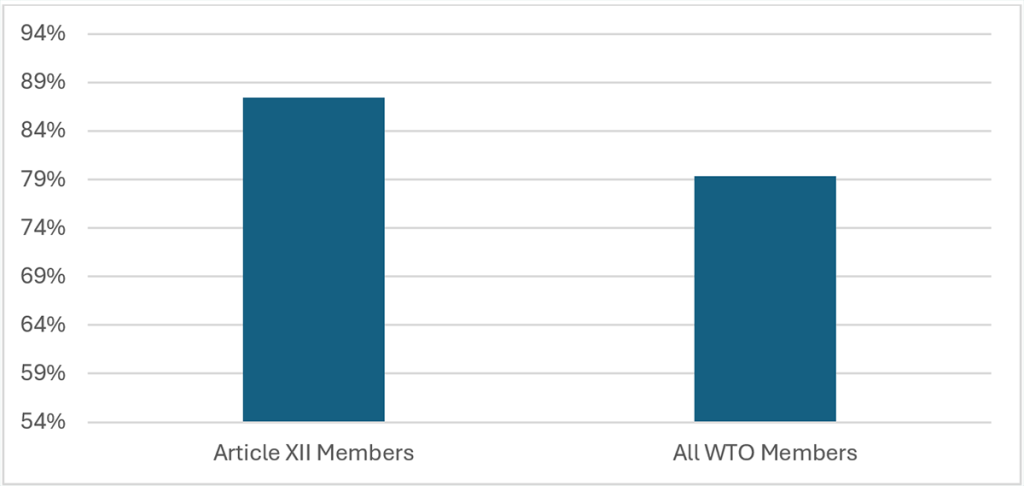

With the aim of lowering trade and transaction costs, the TFA came with quick wins to tackle the endogenous costs (costs related to national policies) faced by economies. By streamlining processes, border and customs formalities, it aimed to enhance efficiency and facilitate smoother trade, ultimately benefiting participating economies. According to the WTO’s TFA database, the average TFA implementation rate of all of the 38 acceded economies to the WTO is 87.36%, compared to a global average of 79.4%(see Figure 2) .[5] One of the recent findings by the WTO Secretariat is that the TFA has induced a US$ 231 billion increase in international trade between 2017 and 2019. This increase was attributed to mainly trade growth in LDCs, where agriculture growth increased by 17%. The 2024 World Trade Report highlights those economies that undertook more “reform and liberalization commitments” as part of their accession packages realized a 1.5% boost to their annual growth rates and at the same time driving more capital into their economies. The analysis demonstrates that WTO accession leads to trade liberalization and reduction in trade costs. Implementation of the TFA is certainly expected to contribute further to this can therefore likely be a cornerstone in advancing trade-led growth in the short, medium and long run.

Figure 2: WTO TFA Implementation rates - Article XII Members and all WTO Members

Source: WTO Secretariat/TFA Database.

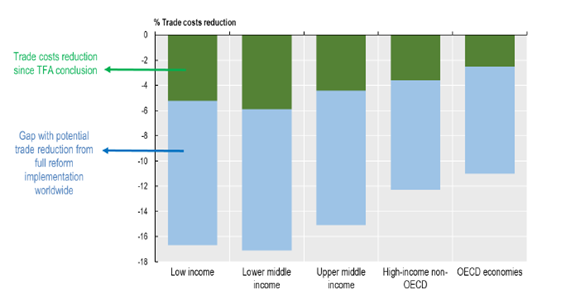

The disruptions caused by (COVID-19) pandemic followed by the geopolitical tensions have increased shipping costs and disturbed supply chains globally, with the developing countries being the most vulnerable. According to UNCTAD’s recent rapid assessment on the shipping disruptions, container shipping costs have more than doubled reaching 122% in February 2024. Nevertheless, the WTO TFA can still be leveraged on to cushion the inflationary effects caused by these exogenous shocks (shocks outside a country’s control). According the WTO’s TFA database, the five least implemented articles are vital for reaping the optimum benefits of facilitating trade: (i) single window; (ii) test procedures; (iii) border agency cooperation; (iv) risk management and (v) authorized operators. The need to advance implementation of the WTO TFA to reduce trade costs in low income and lower income countries is also evident in the forthcoming work of Sorescu[6] from OECD that is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Evolving Role of Trade Facilitation in Policies in Reducing Trade Costs

Trade Facilitation Indicators and Digitalization

Trade facilitation indicators are instrumental for policymakers to baseline the current trade facilitation environment, diagnose specific bottlenecks and benchmark against other countries. Moreover, private companies take them into account when taking investment decisions. Therefore, maintaining high scores might impact Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). It is also important to conceptualize between the indicators that measure policy inputs and indicators that measure policy outputs.

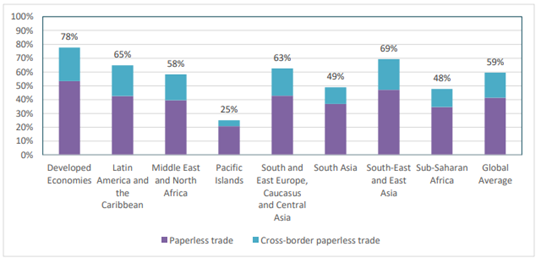

Among the most widely used indicators that measure policy inputs in trade facilitation are the: (I) UN Global Survey on Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation; (II) OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators; (III) the WTO TFA Database and (IV) the recently published ‘UN Trade Digitalization Index’. All the following indicators take the WTO TFA as a basis of measurement, with different implementation criteria such as transparency, formalities and institutional arrangement and cooperation. The most recent published indicator, the UN Trade Digitalization Index which stems from the UN Global Survey on Digital and Sustainable Trade Facilitation looks into the digitalization of trade processes and places them into two categories: paperless trade and cross-border paperless trade. The data shows wide disparities between regions and countries, showcasing the need to boost implementation of the digitalization of trade procedures such as in automated customs systems, single windows and electronic submissions. According to the 2023 average trade digitalization rates around the world, the global average is at 59% as can be seen below in figure 4.[7]

Figure 4: Average Trade Digitalization Rates around the World

On the other hand, the more commonly used indicators that measure policy outputs are: (I) UNCTAD General and Maritime Profiles; (II) World Bank Business Ready Report; (III) World Bank Logistics Performance Index and (IV) World Bank Doing Business Report. [8] The policy output indicators measure the impacts of the trade facilitation ecosystems in the respective countries. This can include the number of documents required for an export/import procedure, number of days to export/import and general business and investment friendliness indicators. The UNCTAD Maritime and Country profiles cover shipping connectivity and macroeconomic indicators respectively.

UNCTAD’s Work Programme on Trade Facilitation

UNCTAD has been at the forefront of providing technical assistance and capacity building to National Trade Facilitation Committees (NTFCs) worldwide. In 2023, UNCTAD has provided technical assistance to more than 70 partner countries and 10 Regional Economic Communities. 200 webinars with over 1,100 participants from private and public sectors have been conducted in their e-learning platform in 2023. The Reform Tracker, an online project management tool for NTFCs has been implemented in more than 25 countries, supporting their trade facilitation reforms. UNCTAD also maintains the NTFC database containing data on 135 NTFCs around the world, which is directly linked to the WTO TFA database. Trade Information Portals, Trade Facilitation Roadmaps, Procedure Analysis & Simplification and Advisory Services have all been part of UNCTAD’s work in supporting countries in their trade facilitation agenda.

Acceding governments should and can leverage on TFA implementation

Acceding governments should not wait until they join the WTO to implement the TFA since it is part of the WTO acquis. The earlier acceding governments implement measures to facilitate their trade, the faster their economies will integrate into regional and global value chains, help them with export diversification, regional economic integration and attract foreign investment. Acceding governments should present their TFA implementation plans, and technical assistance needs such as Comoros and Timor-Leste. Uzbekistan plans to present its TF implementation plan to the TFA Committee at WTO this October 2024. Moreover, TF measures are now part of many regional and bilateral trade agreements such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). It is important to establish Trade Facilitation Roadmaps and effectively manage and coordinate implementation through National Trade Facilitation Committees backed by strong political leadership and relevant stakeholders to effectively implement TF reforms. Acceding governments should make use of the myriad tools and assistance available for them from UNCTAD and other partner agencies working in the area of trade facilitation.

[1] Specific steps include (a) the establishment of a Working Party, (b) a memorandum from the applicant country detailing its Foreign Trade Regime, (c) negotiations, both bilateral on schedules of specific goods and services commitments, and multilateral as necessary, and (d) the Working Party’s Report, draft Decision, and Protocol of Accession to be approved by existing members.

[2] Prior to 1995, under the WTO's predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), Contracting Parties automatically became members of the WTO.

[3] From establishment of the Working Party

[4] The Uruguay Round was the 8th round of multilateral trade negotiations conducted within the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, spanning from 1986 to 1993 and embracing 123 countries as "Contracting Parties". - WTO

[5] Except for Comoros and Timor-Leste as they are still not in the database and Yemen as it has not yet ratified the TFA.

[6] Paper is forthcoming and was obtained from a WTO Workshop: GVCs for LCDs, proposed by the European Union.

[7] Trade Digitalization Index: A new tool for assessing the global state of play in the digitalization of trade procedures – Yann Duval et al.

[8] The World Bank Doing Business was suspended due to a number of irregularities that were reported regarding changes to the data in the Doing Business 2018 and Doing Business 2020 reports, published in October 2017 and 2019 respectively.

Contact Authors:

Mena Hassan| Senior Trade Policy and Trade Facilitation Expert| Accessions Division, WTO| mena.hassan@wto.org

Tarig Ahmed| International Economist| Trade Facilitation Section, UNCTAD| tarig.ahmed@un.org