Pamela Coke Hamilton, Director of the Division on International Trade and Commodities and Janvier Nkurunziza, Commodity Research and Analysis Section

As the COVID-19 virus continues its gallop across the world, we are forced to constantly reassess our expectations of both the human and economic costs that it will bring.

Indeed, the world is now reaching a point where unilateral decisions by food exporters and falling national revenues could have devastating effects for food-insecure countries, compounding health problems for already vulnerable citizens.

Earlier this year, when the virus was more or less limited to China and a few of its neighbours, analysts were more focused on disruptions to global manufacturing value chains, foreign direct investment, and the likely impact of the Chinese economy’s slowdown on global GDP, given the weight of China in the global economy.

Consequently, at the beginning of the pandemic, little emphasis was placed on food security, given the expectation that food markets would be well supplied, as cereal stocks would reach their third highest level on record and that, as a result, export availabilities for wheat, maize, rice and soybeans would easily meet anticipated demand.

Devastating effect on food security

It is now feared that the COVID-19 pandemic could have a devastating effect on food security if major cereal exporters adopt trade barriers or export bans, as experienced during the 2007-2008 food crisis, or if coronavirus’ effects on the labour force and logistics become important.

In addition, for countries that strongly rely on food imports, food security is vulnerable to revenues lost as a result of slowing economic activity caused by COVID-19.

Developing countries, particularly small island development states (SIDS), dependent on tourism have already experienced a precipitous collapse in their revenues given that international travel has come to a halt. These losses make it more difficult to pay for the imported food required for survival in these countries.

How likely will COVID-19 cause shocks to food markets? As the pandemic worsens and countries across the world impose lockdowns and close their borders, there is growing fear that food markets are going to be affected by logistical constraints and labour shortages, thereby putting pressure on prices.

Cereals imports are spread across a very large number of countries in all regions - China alone accounts for more than 5% of total imports - whereas only a handful of countries account for the bulk of cereals exports.

We have already seen that as a result of fear of potential logistical disruptions in supply markets in China, the biggest importer of soybeans, soybean futures prices increased by 5% between 27 March and 30 March. Soymeal, soyoil, palm oil and other food commodities also saw price increases.

The United States and the Russian Federation alone represent a quarter of cereals exports. Adding exports by India, Argentina, Australia and Ukraine, a total of six countries where COVID-19 is in its expansion phase account for more than half of total cereals exports.

Global food security in peril

Export restrictions imposed by any of these major actors can potentially imperil global food security, especially in atomized net food-importing developing countries.

Given the United States’ most recent uses of trade restrictive measures against its partners and the Russian Federation’s wheat export taxes during the 2007-2008 food crisis and an export ban in 2010, this does not seem like an implausible scenario.

There are also indications that Kazakhstan and Viet Nam have suspended exports of wheat flour and rice, respectively, as a result of COVID-19.

Food price surges, export bans or revenue loss due to economic contraction can all have grave consequences on food security.

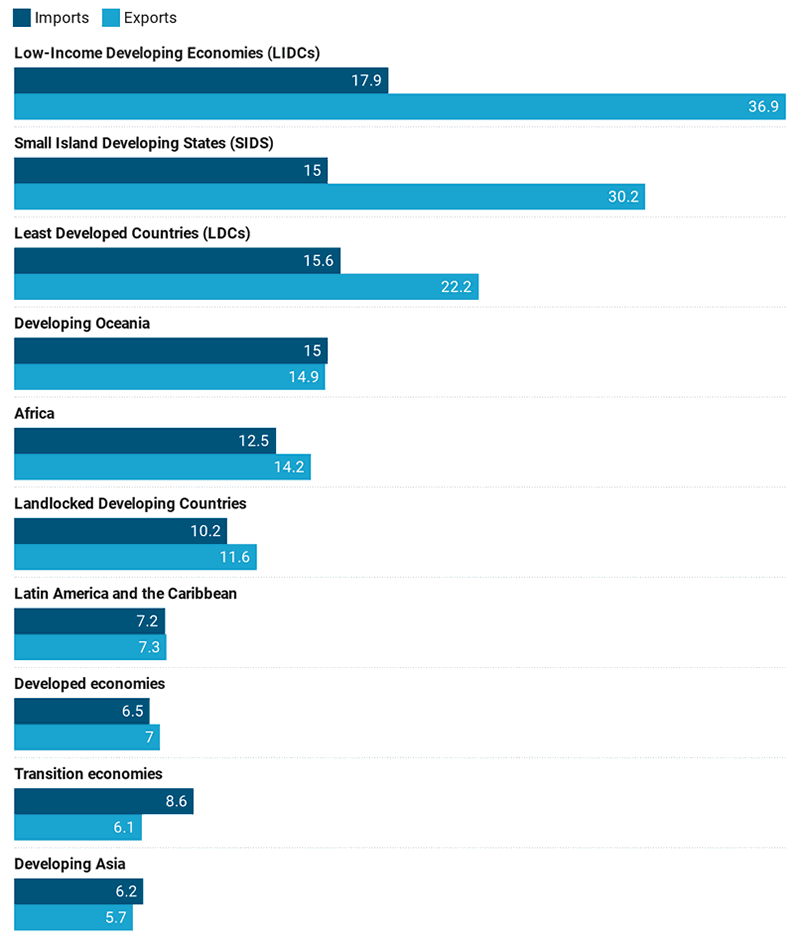

Using the most recent data on food import dependence, UNCTAD finds that low-income countries devote 37% of their merchandise export revenue to food imports, more than five times the share by developed economies. This makes these countries extremely vulnerable to external shocks.

UNCTAD also finds that small island developing states (SIDS) are highly exposed to international food market shocks, while regional distributions of vulnerability show that Africa and Oceania are most exposed.

Ensure free flow of food products

Given these fragilities, major food exporting countries need to respect their commitments under the rules of the World Trade Organization to ensure the free flow of food products and refrain from imposing export bans and other export trade distorting measures that can hamper the availability of food imports in vulnerable food-importing countries.

In addition, national authorities should ensure that transborder movement of food commodities is not hampered by border closures as a way of controlling the spread of COVID-19, and also allow food to come to urban centres from producing regions in order to prevent food shortages and panic buying.

As the pandemic evolves, the international community needs to remain vigilant and ready to take decisive action should food import-dependent developing countries fall victim to overwhelming shocks emanating from international food markets.

As part of this effort, due consideration should also be given to the WTO Ministerial Decision that recognizes that, in case of short-term difficulties in financing normal levels of commercial imports, net food-importing developing countries may be eligible to draw on the resources of international financial institutions under existing facilities, or such facilities as may be established, in the context of adjustment programmes, in order to address such financing difficulties.

(%) 2018