Steve MacFeely, Chief Statistician, UNCTAD

In March 2015, presidents and prime ministers around the world signed up to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. That agenda is the most ambitious development plan ever conceived by the UN. The 169 targets cover just about every dimension of development imaginable, including no less than the total eradication of extreme poverty by 2030. This programme foresees that 232 statistical indicators or performance metrics will be produced by every country in the world to benchmark progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Where will all this data come from?

It’s a pertinent question. Many developing countries still struggle to compile basic economic and social statistics. Is it realistic to expect that developing countries will have the capacity to produce these new indicators? In fact, developed countries will also struggle. About a third of the required indicators are from areas outside traditional official statistics, meaning that no agreed concepts, definitions or methodologies exist.

How much will the SDG indicators cost?

The estimates vary but all exceed existing funding. The Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data believes around $650 million per year is needed to collect SDG data, of which only $250 million is currently funded. PARIS21 estimates that current annual funding of $300 million must be increased to at least $1 billion by 2020.

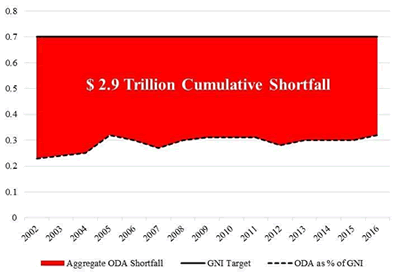

To put these numbers in perspective, OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members contribute, on average, $113 billion per year to Official Development Assistance (ODA). At the International Conference on Financing for Development in 2002, these nations promised to contribute 0.7% of their gross national incomes to ODA. But since 2015 and the start of the 2030 Agenda, average country efforts remain well below the 0.7% target. Today, the cumulative shortfall in ODA (2002–2016) stands at $2.9 trillion in 2016 constant prices. So, in an environment of faltering multilateralism where will the additional funding come from?

Is there another way to solve this problem?

As it happens, there is. The world of data, statistics and information is changing – and fast. Today we are overwhelmed by a deluge of data, coming from a wide variety of sources. Furthermore, a whole host of new statistical compilers have emerged – NGOs, commercial enterprises, social media bloggers and academics. People now talk about a “data revolution”. But now it’s time to move from words to actions: time to harness the work and intellectual creativity of those outside the official statistics tent.

So what’s the solution?

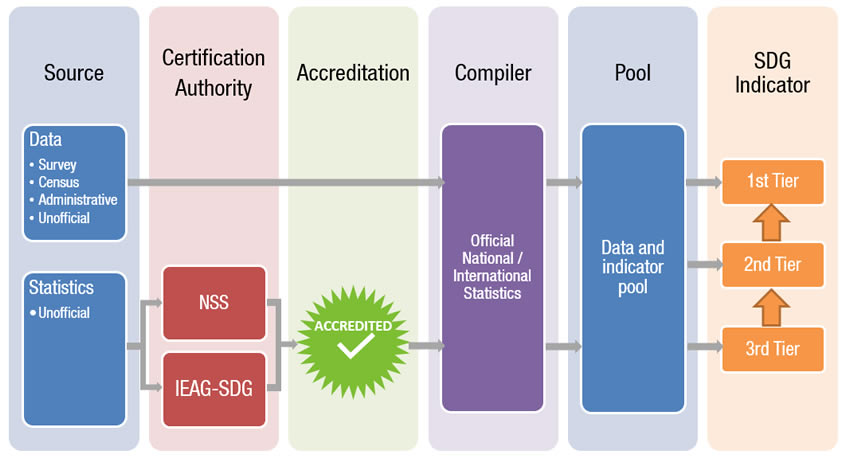

Why not introduce a mechanism to certify unofficial statistical indicators as official? The idea of using unofficial data to compile official statistics is not new. National and international statistical offices use unofficial data every day as inputs to compiling official statistics. Why not go a step further and use already compiled unofficial statistics to fill some of the gaps in official statistics?

We propose that a body with the authority and competence to certify statistics as “fit for purpose” should be mandated by the United Nations. Compilers of unofficial statistics could then bid to have their indicators certified as official for SDG purposes.

What does “fit for purpose” mean?

Fit for purpose means that an indicator or statistic adheres to pre-defined quality and metadata standards. These standards would be set in advance and open to all. Prospective compilers of official SDG indicators would be required to guarantee that they can supply those indicators for, at least, the lifetime of Agenda 2030. In practical terms, this means being able to supply, at a minimum, the statistic on an annual basis for the years 2010–2030. Their input data and methodologies must also be non-proprietary, available to all and open to scrutiny (subject to sensible confidentiality constraints).

Are there any risks with such a proposal?

Yes, of course. Every bold initiative is to some extent a gamble. All big decisions involve risk. The trick is to mitigate against the downsides. That means not adopting the idea blindly but carefully weighing up the pros and cons of different options and strategies. There are already concerns regarding reduced funding for official statistics and surrendering ground to other information providers. Naturally, some may fear this proposal will add fuel to the fire. But it may be necessary to open up and surrender a position of dominance today in order to survive tomorrow. For better or worse, the 2030 Agenda has created a vacuum. If this data vacuum is not filled by official statistics, it will be exploited by someone else. In a rapidly changing and increasingly competitive data world, official statisticians must learn to collaborate.

Has anything like this been tried before?

As a matter of fact, it has. Many of our greatest scientific discoveries have come from unofficial or supposedly amateur scientists. Some famous examples are John Harrison (H1 ships chronometer), Michael Faraday (electrolysis and electromagnetic induction), Gregor Mendel (the dominant/recessive qualities of genes), William Herschel (telescopic lenses) and Charles Darwin (theory of evolution). Amateurs like these were able to make such important contributions to science, and have their work recognized, because bodies such as the Royal Society, the Royal Astronomical Society or the Académie des sciences were willing and able to authenticate their findings. We can learn from this experience. Just as professional scientists did not have a monopoly on scientific wisdom in the past, official statisticians do not have a monopoly on information today. The UN needs to create a modern-day Académie des sciences.

Is this proposal consistent with philosophy of 2030 Agenda?

Yes, it is. The 2030 Agenda emerged from a globally inclusive, open and democratic process. In line with this open philosophy, compilation of SDG indicators could also be open and inclusive. To an extent it already is, in that anyone can propose indicators or comment on existing proposals. To date, it has been envisaged that compilation will be the exclusive permit of official statisticians. But what if the power and knowledge of unofficial data and unofficial statisticians could be harnessed? That would indeed be a data revolution.

Read the original article on the World Economic Forum

Follow them: @wef on Twitter | World Economic Forum on Facebook