An internationally agreed fair and efficient sovereign debt workout mechanism is of paramount importance to mitigate the damage from financial shocks, restore debt sustainability and reduce the threat of contagion, the UNCTAD Trade and Development Report, 20151 argues. While bankruptcy laws are an integral part of any healthy market economy at the national level, no counterpart exists at the international level to address sovereign debt crises.

The current system of sovereign debt resolution is fragmented and ad hoc. This has created a situation in which national Governments are left to their own devices to face a multitude of private creditors, some of whom seek to exploit the current vacuum of international rules and action to speculate on sovereign debt, using litigation to extract exorbitant profits. By doing so, these non-cooperative actors make sovereign debt restructurings more difficult than they already are, harm other creditors’ interests and undermine the prospects for economic recovery in debtor economies.

The UNCTAD report explores the pros and cons of a range of routes – market-based, soft-law and statutory – towards a sovereign debt workout mechanism that can rally the support of Governments and investors alike.

“Such a mechanism aims not only at facilitating an equitable restructuring of debt that can no longer be serviced according to the original contract, but also helps to prevent financial meltdown in countries facing difficulties servicing their external obligations,” UNCTAD Secretary-General Mukhisa Kituyi said.

The urgency of UNCTAD’s call is justified by the highly fragile state of the global economy: emerging economies – the main contributors to global growth since 2011 – are now facing difficulties, while developed economies are still failing to produce more than lacklustre growth performances eight years after the global financial crisis.

This state of fragility is unsurprising in a global economy that continues to exhibit an unhealthy dependence on debt. During the years of the “great moderation” (1985–2005), global debt levels rose from around $21 trillion in 1984 to $87 trillion by 2000, and to a staggering $142 trillion by the end of 2007. Since the financial crisis in 2007/08, another $57 trillion has been piled on top. This context strengthens the case for appropriate mechanisms to deal with sovereign debt crises, the report says.

For now, public sector borrowing in advanced economies leads the way, as is inevitable after a serious economic crisis. Nonetheless, as the report shows, developing country debt – both public and private – is on the rise too, not least as after 2008 developing and transition economies became the most attractive destination for private capital in search of positive returns.

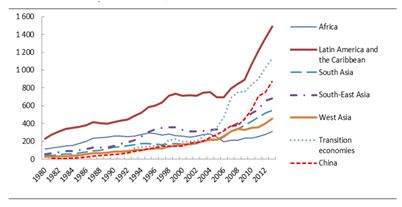

External sovereign debt indicators improved in many developing countries during the 2000s due to booming exports, higher fiscal revenues and strong gross domestic product growth. Gradually rising external debt levels in most developing countries (see figure) will be more difficult to service, however, in an economic environment characterized by falling commodity prices, rising interest rates, currency depreciations and a slowdown in global gross domestic product growth.

For the moment, one issue to watch closely is that of external corporate debt in emerging markets, which has tripled since 2008 to more than $2.6 trillion. Easy access to credit by private corporations in emerging markets, coupled with ineffective monitoring by creditors, can quickly turn sour though, if investor sentiment turns against those markets.

As witnessed in almost all major debt crises in emerging economies since the 1980s and more recently also in some eurozone economies, unsustainable private debt is bound to produce sovereign debt crises. Rather than being brought on by irresponsible fiscal profligacy, sovereign debt crises in developing and transition economies are more likely the result of Governments stepping in to bail out delinquent private sector borrowing, the UNCTAD report underlines.

Progress can be achieved by improving existing sovereign debt bond contracts – to minimize scope for hold-out investors and to ensure collective creditor interests dominate their actions – as well as by promoting soft-law guiding principles at the international level on how best to conduct sovereign debt restructurings.

In the long run, a statutory – multilateral treaty-based – approach that defines a set of binding rules and norms, agreed in advance as a part of an international debt workout mechanism, is however the preferred option that is both efficient and fair, the report concludes.

Graph 1: External debt in selected country groupings and China, 1980–2013

(Billions of current dollars)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on the World Development Indicators database

of the World Bank and national sources.

Note: Aggregates are based on countries that have a full set of data since 1980 (except for transition

economies, where the cut-off date used is 1993).

Report: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tdr2015_en.pdf

Overview: http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tdr2015overview_en.pdf