In 2021, the global economy will bounce back with growth of 5.3%, the fastest in nearly 50 years. The rebound is, however, highly uneven along regional, sectoral and income lines, according to UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Report 2021.

© Poco_bw / africaphotobank.com

- Growth deceleration next year could prove sharper than expected if policymakers lose their nerve or heed misguided calls for deregulation and austerity.

- Policymakers in advanced economies have not yet woken up to the size of the shock to developing countries or its persistence. Many countries in the South have been hit much harder than during the global financial crisis, while their now-heavier debt burden reduces their room for fiscal policy.

- The pandemic response in developed countries has activated a resurgent state and suspended fiscal constraints, but international rules and practices lock developing countries into pre-pandemic responses and a semi-permanent state of economic stress.

UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Report 2021, released on 15 September, says this year will see the global economy bounce back thanks to the continuation of radical policy interventions begun in 2020 and a successful (if still incomplete) vaccine roll-out in advanced economies. Global growth will hit 5.3%, its fastest rate in nearly five decades.

The recovery, however, is uneven across geographical, income and sectoral lines. Within advanced economies, the rentier class has experienced an explosion in wealth, while low-earners struggle.

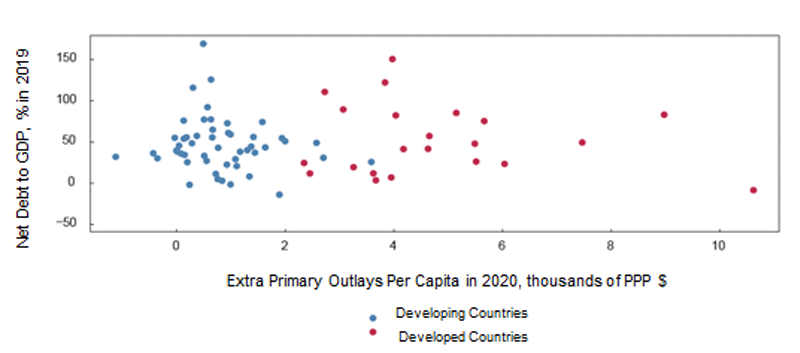

Constraints on fiscal space (Figure 1), lack of monetary autonomy and access to vaccines are holding many developing economies back, widening the gulf with advanced economies and threatening to usher in another lost decade.

Figure 1: Additional primary outlays in 2020 relative to inherited debt ratios in developing and developed economies

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on IMF database.

“These widening gaps, both domestic and international, are a reminder that underlying conditions, if left in place, will make resilience and growth luxuries enjoyed by fewer and fewer privileged people,” said Rebeca Grynspan, the secretary-general of UNCTAD.

“Without bolder policies that reflect reinvigorated multilateralism, the post-pandemic recovery will lack equity, and fail to meet the challenges of our time.”

UNCTAD’s proposals, outlined in more detail below, are drawn from the lessons of the pandemic, and include concerted debt relief and even cancellation in some cases; a reassessment of the role of fiscal policy in the global economy; greater policy coordination across systemically important economies; and bold support for developing countries in vaccine deployment.

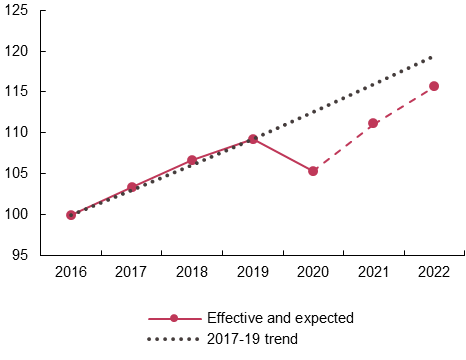

In 2022, UNCTAD expects global growth to slow to 3.6%, leaving world income still 3.7% below where its pre-pandemic trend would have put it (Figure 2); an expected cumulative income loss of about $13 trillion[1] in 2020-22. Timid policy or, even worse, backsliding, could pull growth down further.

Figure 2: World output level, 2016–2022

(Index numbers, 2016 = 100)

Source: Trade and Development Report 2021.

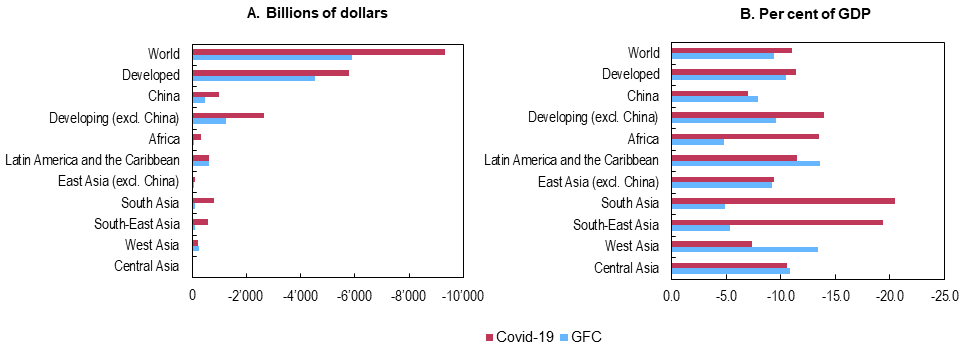

Across the world, but particularly in developing regions, the damage from the COVID-19 crisis has been greater than that from the global financial crisis (GFC), most notably in Africa and South Asia (Figure 3).

Even barring significant setbacks, global output will only resume its 2016-19 trend by 2030. This fact conceals the deeper problem that the pre-COVID-19 income growth trend was itself unsatisfactory; average annual global growth in the decade after the GFC was the slowest since 1945.

Figure 3: The economic impact of GFC, 2009–2010, vs. Covid-19, 2020–2021

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on official data and estimates generated by United Nations Global Policy Model.

Note: Estimated loss from GFC corresponds to the accumulated income loss of 2009 and 2010, relative to 2006 to 2008 trend; and the estimated loss from COVID-19 corresponds to the accumulated income loss of 2020 and 2021, relative to 2017 to 2019 trend.

Temporary price hikes caused by unsynchronized supply and demand side pressures may become excuses to reverse policies required to sustain recovery in advanced economies. Despite a decade of massive monetary injections from leading central banks, inflation targets have been missed and, even with the current strong recovery in advanced economies, there is no sign of a sustained rise in prices.

After decades of a declining wage share, real wages in advanced countries need to rise well above productivity for a long time before a better balance between wages and profits is achieved again. That said, UNCTAD believes the rise in food prices could pose a serious threat to vulnerable populations in the South, already financially weakened by the health crisis.

Globally, international trade in goods and services has recovered, after the overall flow dropped by 5.6% in 2020. The downturn proved less severe than had been anticipated, as month-on-month merchandise trade flows in the latter part of 2020 rebounded almost as strongly as they had fallen earlier.

The report’s modelling projections point to real growth of global trade in goods and services of 9.5% in 2021. Still, the recovery has been extremely uneven, and scars will continue to weigh on the trade performance in the years ahead.

In 2021, the positive trajectory of commodity prices from the trough observed in the second quarter of 2020 has continued. The aggregate commodity index registered an increase of 25% from December 2020 to May 2021, mainly due to the price of fuels, which surged by 35%, while that of minerals, ores and metals registered an increase of 13%.

“The pandemic has created an opportunity to rethink the core principles of international economic governance, a chance that was missed after the global financial crisis,” said Richard Kozul-Wright, director of UNCTAD’s globalization and development strategies division.

“In less than a year, wide-ranging policy initiatives in the United States have begun to effect concrete change in the case of infrastructure spending and expanded social protection, financed through more progressive taxation. The next logical step is to take this approach to the multilateral level.”

Internationally, US support for the new special drawing rights (SDR) allocation, global minimum corporate taxation, and a waiver of vaccine-related intellectual property rights in the World Trade Organization hold out the possibility of a renewal of multilateralism.

But this will need much stronger backing from other advanced economies and the inclusion of developing country voices if the world is to tackle the excesses of hyperglobalization and the deepening environmental crisis in a timely manner.

The biggest risk for the global economy is that a rebound in the North will divert attention from long-needed reforms without which developing countries will remain in a weak and vulnerable position.

TDR 2021 draws four main lessons from the pandemic

Eighteen months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is waking up to the indispensable role of international cooperation in achieving economic resilience, a principle endorsed at Bretton Woods when the multilateral system was founded. But the resolve to rebalance the global economy and reform the international economic architecture is still missing.

First, any talk of financial resilience in developing countries would be premature since in many cases investment flows remain volatile and the burden of indebtedness intolerable. Although spiralling sovereign debt crises were avoided in 2020, developing countries’ external debt sustainability deteriorated further.

That higher interest rates could spark a run on developing country assets and balance-of-payments problems reflects just how little has changed since the GFC. This fragile state of affairs heightens external solvency and international liquidity constraints.

Over the coming years, pressures on external debt sustainability will persist because many developing countries face a wall of upcoming sovereign debt repayments in international bond markets.

Together, developing countries (excluding China) face total repayments on sovereign bonds already issued to a value of $936 billion until 2030, the year earmarked for achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

UNCTAD calls for concerted debt relief and in some cases outright cancellation in order to reduce the debt overhang in developing countries and avoid another lost decade for development.

Second, the pandemic has seen an emergent consensus around the need for significant public sector intervention, but there is less agreement on what this will involve beyond countercyclical measures. There is a risk that expansionary fiscal measures will be regarded only as fire-fighting tools, while, in fact, they are critical instruments of long-term development.

UNCTAD calls for the political space created by the pandemic to be used to re-assess the role of fiscal policy in the global economy, as well as the practices that have widened inequalities.

Third, delivering the necessary support to build back better will require much greater policy coordination across systemically important economies; reforms to the international economic architecture that were promised after the 2008-09 crisis but were quickly abandoned in the face of resistance from the rentier class.

Fourth, the reluctance of other advanced economies to follow the US lead on the vaccine waiver is not only a worrying sign of disjointed obduracy in the North; it is a particularly costly one for already financially constrained economies. On one recent estimate, the cumulative cost of delayed vaccination will, by 2025, amount to $2.3 trillion with the developing world shouldering the bulk of that cost.

Renewed international support is needed for developing countries, many of which face a spiraling health crisis, even as they struggle with a growing burden of debt and face the prospects of a lost decade.

[1] Based on 2015 constant dollars and exchange rates.