Written by Brigitte Daudet and Yann Alix, Article No. 98 [UNCTAD Transport and Trade Facilitation Newsletter N°96 - Fourth Quarter 2022]

© Jan Hoffmann

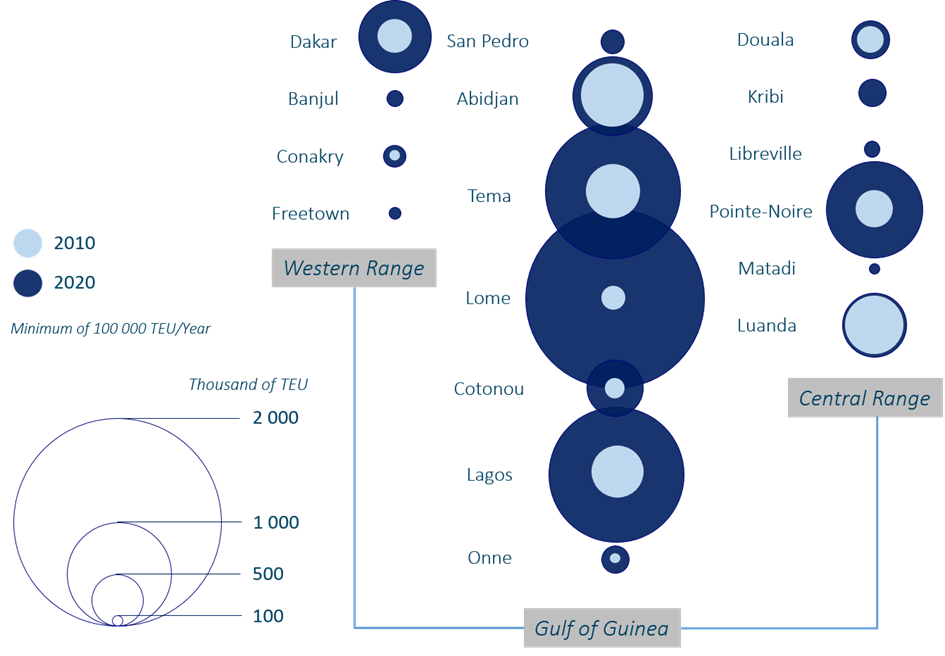

Africa accounts for less than 5% of international maritime trade and the total throughput of all West and Central African (WCA) port range represents less than 1% of the world total handling with 10 million TEU in 2021 (Alix & Daudet, 2021). However, the geographical configuration and the historical construction that have formed the current borders have made it possible for 17 countries ranging from Senegal to Angola, to have direct access to the ocean, through more than 30 international trade ports. Among them, only 11 ports handle more than 100,000 TEU in 2010 and then 17 ports a decade later, with the highest concentration in the Gulf of Guinea, which benefited from the most populated hinterlands. The port of Lomé has become the regional leader as its volumes multiplied by 7 in a decade due to the transhipment strategies of the Italian-Swiss shipping company MSC Shipping. The visual representation of the linear method reveals the growth size of the transhipment ports relative to the so-called gateway ports such as Abidjan and Dakar that have lost relative market share between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total Throughput on the Dakar-Luanda port range (2010/2020)

Source: Authors based on Drewry Maritime Research 2022 & SEFACIL Foundation Database 2022.

A niche market controlled by few Western European shipping companies

West and Central African (WCA) markets remain fragmented with cross-border logistics fluidity hampered by administrative constraints and customs barriers. As a result, maritime services in the WCA have been delivered by small and mid-sized vessels that provided direct “quick stopover” services from port to port. Such maritime services are able to accommodate the nautical constraints faced by certain ports while guaranteeing routes for import flows that are systematically higher than export flows across the WCA markets. In the 2010s, shipping lines drastically modified their strategies to take advantage of the modernization/extension of container dedicated terminals motivated by the liberalization policies promoted by the International Monetary Funds and The Word Bank Group. The average size of a containership on the Asia/Oceania route has increased threefold with the deployment of 10,000+ TEU ships by CMA-CGM at its regional hub in Pointe-Noire and, above all, the strengthening of MSC shipping's direct Africa Express service with 14,000+ TEU units in Lomé (Daudet & Alix, 2022).

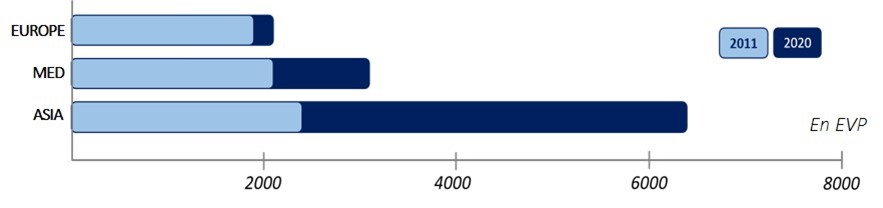

This increase in containership size is also noticeable in the Mediterranean with the pivotal role of intercontinental hubs in the Strait of Gibraltar (Algeciras in Spain and Tangier Med in Morocco). Cross-trade management by global shipping lines on East-West and North-South services at Tangier Med has had the effect of improving maritime container connectivity in WCA markets. The decline of market share on the maritime route between Europe and WCA explains the small increase in average vessel size, especially as shipping lines prioritize intermediate port calls in the western Mediterranean to serve Dakar-Luanda range (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average size of container ships deployed on the three main routes connecting the Dakar-Luanda Range

Source: Authors based on Dynamar 2011 & 2022 reports.

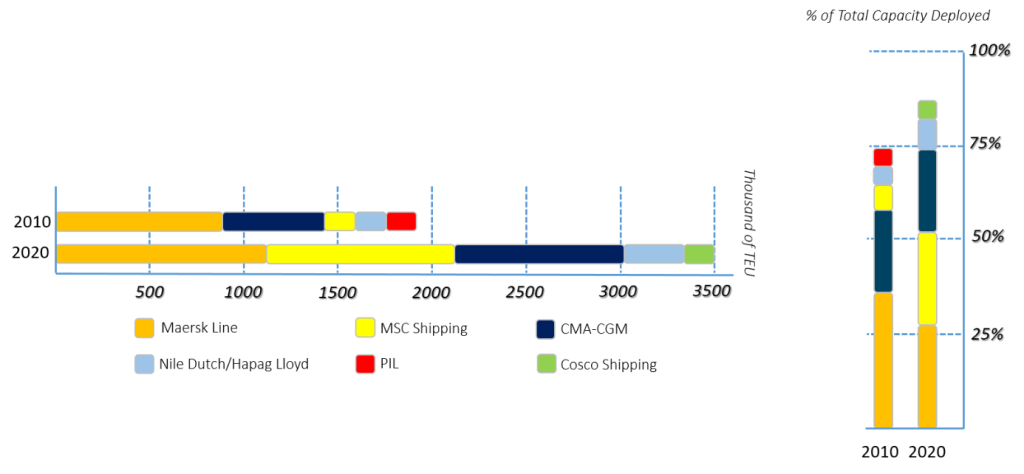

Over the last decade, it is worth noting that the total capacity deployed by shipping lines has increased by 40% to reach 4 million TEUs in 2020. This increase in volume is being driven by the top five shipping lines, to the disadvantage of regional and dedicated small operators, often specializing in the niche markets of the WCA. While 32 companies’ transporting containers operate on the Dakar-Luanda market in 2010, only 20 remains in 2020.

The top three global shipping lines are also those that dominate the capacities and market shares of the Dakar-Luanda range. Maersk Line, MSC Shipping and CMA-CGM have increased their consolidated market share from 54% in 2010 to 74% in 2020. The world leader MSC Shipping aims to overtake Maersk Line as the leading shipping line on the African continent in 2022. According to Dynamar, Maersk Line deployed 1,124,800 TEU on WCA against the 1,012,400 TEU for MSC Shipping and 892,500 TEU for CMA-CGM in 2020. Cosco shipping has taken the 5th place from PIL with 156,300 TEU while Hapag-Lloyd's consolidated capacity reaches 334,200 including Nile Dutch’s fleet. The market share of small and medium-sized operators (outside the top five) has decreased from 25% in 2010 to 15% in 2020.

Figure 3: Total capacities and market shares of the TOP 5 container shipping lines on the Dakar-Luanda port range (2010-2020)

Source: Authors based on Dynamar 2011 & 2022 reports.

The WCA-Asia route (including the Indian Subcontinent and the Middle East) represents 53% of all containerized capacity deployed in 2020. European operators are maintaining their leadership with no real competition from Asian shipping lines. Lastly, the strategic alliances known on major East-West shipping routes do not operate on the WCA, but whenever necessary, the slot sharing on vessels reinforces the commercial positioning of the TOP 3 on the WCA market.

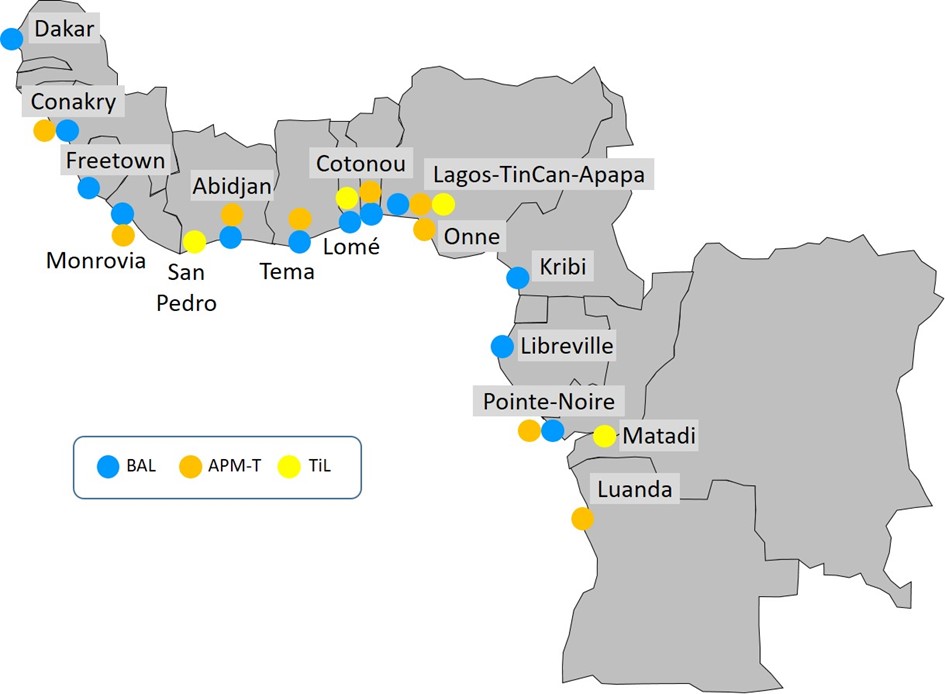

Global Shipping Leaders are also… Global Handling companies on the WCA

The container shipping concentration on the WCA as previously analysed is even more noticeable on terminal activities (Drewry, 2022). Bolloré Africa Logistics (BAL - Bolloré Group), APM-Terminals (A.P. Moller-Maersk) and Terminal Investment Ltd (TiL - MSC Group) hold almost all the container terminals as well as several multipurpose and Ro-Ro installations, apart from a few secondary ports such as Banjul (Gambia) or Bissau (Guinea Bissau), the PTML roll-on/roll-off terminal in Tin-Can or the Equatorial Guinean port activities of Bata/Malabo. The only notable exception involves the case of Douala International Terminal (DIT), which was historically under a BAL/APM-Terminals concession and was "won" in 2019 by TiL before Official National authorities formally commissioned the Régie du Terminal à Conteneurs (RTC) in January 2020 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: TOP 3 terminal operators on WCA port range

Source: Authors 2022

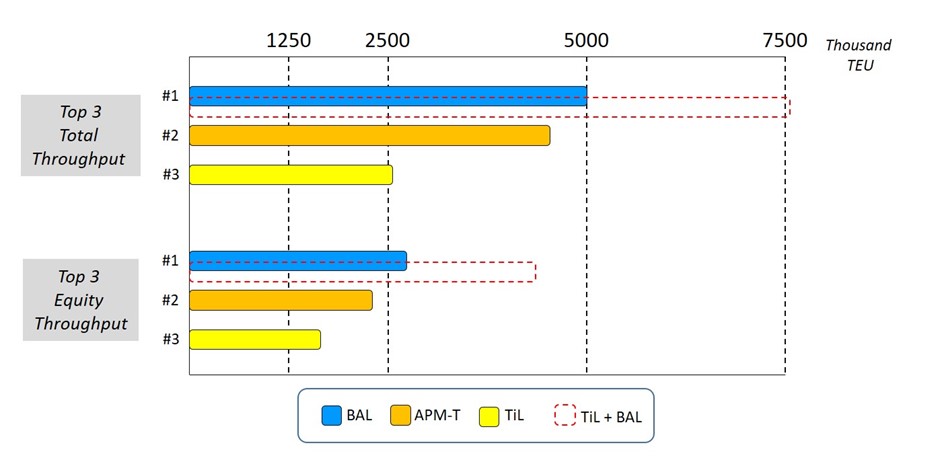

In this competitive landscape, it is worth considering the role of the Dubai-based DP World in the ports of Dakar (Senegal) and Luanda (Angola) and the Filipino ICTSI in Matadi (DRC). Among the Chinese world leaders in container handling operation, they are not so much invested on the African continent, except China Merchants Port who appears alongside TiL on Lome Container Terminal (equity share of 50%), and in capital support of BAL on Tin-Can Island Container Terminal (TICT) in Nigeria and on Kribi Container Terminal (KCT) in Cameroon. This analysis highlights that the two largest shipping companies can count on their port subsidiaries, which are by far the two largest container handling entities since the acquisition of BAL by TiL for €5.7 billion in 2021. The new TiL-BAL business unit accounts for the equivalent of 7.5 million containers in 2020 if we refer to the cumulative results of the two operators (with an estimated of 8 million TEUs in 2021).

Figure 5: Total and equity throughput of the TOP 3 in WCA markets – 2020

Source: Authors based on Drewry Maritime Research 2022.

Considering BAL's strategic and capital-intensive partnerships with APM-Terminals at major terminals such as Téma, Abidjan and Pointe-Noire, the new TIL/APM-Terminals duopoly will control more than 80% of the handling (in total volume and equity) in WCA markets (Figure 5). For countries such as Togo or Côte d'Ivoire that have several terminals, the absorption of BAL by TiL would mean that containerized activities will be vertically controlled by the various maritime, port and logistics entities of the MSC and A.P. Moller-Maersk consortia (Dadie; Silue; Kablan & N'Guessan, 2018).

Discussion : Public regulation and strategic opportunities

The unforeseen consequences of the pandemic crisis included historic spikes in ocean freight rates, operational and strategic adjustments engineered by shipping lines, and the lack of preparedness by various stakeholders to deal with port congestion. Whether in Washington, Beijing, Seoul, or to a lesser extent Brussels, no investigation has succeeded in thwarting the market forces that have created these extreme maritime and port conditions. No regulatory effect nor governmental policy have been able to curb these disruptions, which continue to impact most global value and supply chains. All markets are affected and the WCA has not escaped the adjustments orchestrated by dominant liner shipping companies. Skip calls and reorganization of services, drastic capacity reduction and selective allocation of equipment: West and Central African importers and exporters have been directly affected and none of the numerous regional African institutional organizations has had a say over these modifications and their consequences on final consumers.

This raises the delicate issue of the agility of public policies and their capacity (technical, legal, financial, transactional, etc.) to anticipate, demonstrate and challenge possible abuses of dominant positions. With the above analysis, it is noticeable that the vertical and horizontal concentrations formed by MSC and A-P-Moller-Maersk will influence the relationships of competition and cooperation between all the port authorities of the WCA. Already, the deployment of the Africa Express Service on LCT by MSC Shipping has had the effect of positioning the port of Lomé as one of the leading containerized facilities in the Gulf of Guinea, whereas it was only a minor player a decade ago. National Port Gateways such as Douala and even Libreville have already been connected to various feeder services, changing their maritime connectivity through the deployment of coastal services provided by smaller vessels.

This oligopoly over shipping and handling services can act as a catalyst for modernizing public policy and practice in the WCA. In negotiating the contract terms of terminal concessions, public authorities need to adopt more flexible regulatory tools and methods to provide themselves with greater resilience and effectiveness in defending sovereign interests (Thorrance, 2019). The engineering principles of contractual financial regulation, tariff revision mechanisms and methods of renegotiating commitments are instruments that public authorities must harness in order to take maximum advantage of the private operators’ potential. The current structural oligopoly that is being established in WCA over the past years may provide opportunities to adjust specific tariff policies on transhipment volumes, intra-African short sea shipping services or to review traffic commitments on a long-term perspective. To do this, it is necessary to have public decision-makers with sharpened skills on these sensitive and strategic subjects and strengthening the know-how of the public elites in charge of preserving national socio-economic interests, starting with the crucial port interfaces.

References:

Dadie, A.F., Silue, K., Kablan N’Guessan, H.J., 2018. Stratégies de développement du groupe AP Moller-Maersk sur la côte ouest-africaine. In: Moderniser les ports ouest-africains. Enjeux et Perspectives. SEFACIL Foundation. Collection Afrique Atlantique. Editions EMS, Caen, pp. 57-76.

Daudet, B., Alix, Y., 2022. Croissance portuaire et connectivité maritime. Perspectives Portuaires Africaines. Volume 6. Septembre. 4p.

Drewry Maritime Research, 2022. Global Container Terminal Operators. Annual Review and Forecast. Annual. Report 2021/2022. London. UK. 285p.

Dynamar, 2022. The West Africa Container Trades 2022. April 2022. Alkmaar. The Netherlands. 262p.

Hoffmann, J., 2021. Long term trends in ports and maritime trade: The pas, the present, and Africa’s future. Forum Africain des Ports 2021. 3rd Edition. 21 & 22 October. Douala. Cameroon. 55p.

Thorrance, L., 2019. Les investissements des multinationales privées et institutions financières dans l’économie maritime et portuaire des membres de l’AGPAOC. 40ème Conseil de l’Association de Gestion des Ports de l’Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre. Réunion des Directeurs Généraux. Lomé. Togo

Authors:

Brigitte Daudet | METIS LAB – Normandy Business School | bdaudet@em-normandie.fr

Yann Alix | Fondation SEFACIL | yann.alix@sefacil.com