- Developing countries are already suffering relative economic losses three times greater than high-income countries due to climate-related disasters.

- Adaptation costs for developing countries have doubled in the last decade as a result of inaction. These will only rise further as temperatures increase, reaching $300 billion in 2030 and $500 billion in 2050.

- Adaptation is less a matter of risk management and more one of development planning; and here the state has to play a key role as the best platform to prepare for climate impacts.

2021 has been another year of extreme climate events; more intense heatwaves, increasingly powerful tropical cyclones, prolonged droughts and higher sea levels are unavoidable, with rising global temperatures bringing with them ever greater economic damage and human suffering.

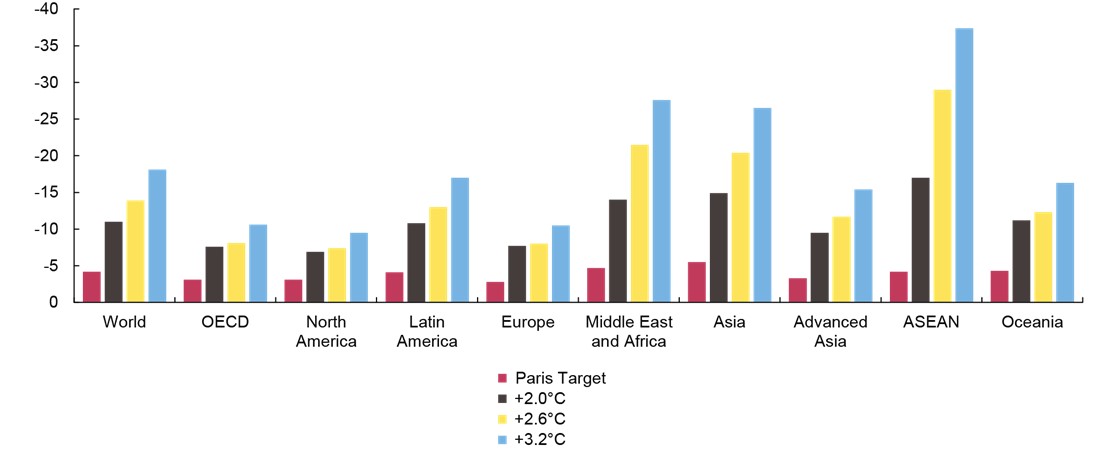

In many developing countries vulnerability to economic and climate shocks are compounding each other, locking countries into an eco-development trap of permanent disruption, economic precarity and slow productivity growth. The greater the rise in global temperatures, the greater the damage to countries in the South (see Figure).

Figure: Mid-century GDP losses by region generated by global warming

(per cent)

Released today, the second part of UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Report 2021 calls for a transformative approach to climate adaptation, with large-scale public investment programmes to adapt to future as well as current threats, and green industrial policies to drive growth and job creation.

UNCTAD Secretary General Rebeca Grynspan says: “The Report demonstrates that sufficient action to adapt to the climate challenge will require a transformed approach that is proactive and strategic rather than simply retroactive. But developing country governments need adequate policy and fiscal space to mobilize large-scale public investment to face future climate threats, while ensuring these investments complement development goals.”

Climate adaptation: More than a risky business

Most of the agenda-setting discussion on the climate has focused on mitigation, leaving adaptation a poor cousin. This is proving short-sighted and increasingly costly, particularly for the developing world where climate shocks are damaging growth prospects and forcing governments to divert scarce resources from productive investments.

At all levels of development, the advice has been to strengthen resilience to shocks by improving data gathering and risk assessment techniques to better protect existing assets and by providing temporary financial support when shocks materialize.

But the report argues that adaptation is less a matter of risk management and more one of development planning. Risk management measures can provide partial resilience to current climate hazards, but these interventions preserve structures that leave developing countries in a state of permanent vulnerability and crowd out more forward-looking options.

According to Richard Kozul-Wright, director of UNCTAD’s globalization and development strategies division, and lead author of the report, “Climate adaptation and development are inextricably connected and policy efforts to tackle adaptation must acknowledge this in order to have a sustainable and meaningful impact.”

The only lasting solution, he suggests, “is to establish more resilient economies through a process of structural transformation and reduce the dependence of developing countries on a small number of climate-sensitive activities.”

Retrofitting the developmental state

The report proposes a “retrofitted” developmental state, empowered to implement green industrial policies and tuned to local economic circumstances, as the best way forward. Activities related to renewable energy production and the circular economy can, the report suggests, operate at a low scale, opening business opportunities for small firms and rural areas, help to diversify economic production structures and reduce many countries’ dependence on the production of a narrow range of primary commodities. This could, in turn, enlarge the tax base and foster domestic resource mobilization as a source of development finance.

However, domestic resource mobilization will need to be strengthened, including through more active central banks, dedicated public banks and strategic fiscal policies.

Given the systemic nature of the adaptation challenges and the need to ensure more equitable outcomes, the development state needs to become a regulator and coordinator of private green finance and go much further than being simply a de-risking vehicle.

As central banks around the world were able to help support governments directly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the report considers how the post-pandemic recovery period could provide an opportunity to follow this same path in support of climate-related investments.

Still, the scale of adaptation needs and the fact that those who suffer the most are the least responsible for the cause of the problem and least able to pay for them, means advanced economies will need to scale up commitments for adaptation finance (see UNCTAD/PRESS/PR/2021/038).

A development-led approach to climate adaptation

Breaking out of the eco-development trap implies that the climate adaptation challenge in the developing world needs to be approached from a developmental perspective, including the following key features:

- Abandoning austerity as the default policy framework to manage aggregate demand and switching to pro-investment policies.

- Large-scale public investment in building a diversified low-carbon economy, powered by renewable energy sources and green technologies, and where economic activities within and across sectors are interconnected through resource-efficient linkages.

- Adopting a green industrial policy that proactively identifies the areas where the most significant constraints to climate adaptation investment are; channelling public and private investment to these activities; and monitoring whether these investments are managed in such a way as to sustain decent employment and to increase long-term climate security and productivity.

- Adopting a green agricultural policy that protects small producers, provides backward and forward linkages to green industrialization, protects the environment and enhances food security through increased agricultural productivity and income security.

- Using renewable energy production and the circular economy to diversify and reduce dependence on primary commodities. Renewable energy production can economically operate at a low scale, opening business opportunities for small firms and rural areas.

The first part of the Trade and Development Report 2021 report was released in September.

UNCTAD supports developing countries to access the benefits of a globalized economy more fairly and effectively and equips them to deal with the potential drawbacks of greater economic integration.

It provides analysis, facilitates consensus-building and offers technical assistance. This helps countries use trade, investment, finance and technology as vehicles for inclusive and sustainable development.